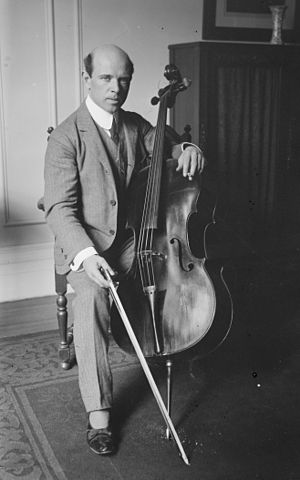

The legendary cellist Pablo Casals was once asked why he continued to practice at the age of 90. “Because” he replied, “I think I’m making progress”.

It is an extraordinary acknowledgement from a man widely regarded as one of the greatest ever cellists. Let’s be clear – Casals was a colossus in his world. Fritz Kreisler (himself a brilliant violinist) called him “the greatest musician ever to draw bow”. He played for English Queen Victoria at 22 and the American president John F. Kennedy in his eighties. And yet we find him, in his nineties, still committed to making progress.

The same question confronts all of us, in any field, who aspire to do something well. We mediators are no exception. The challenge we face is not “Can we improve?” but “How do we improve?”. Casals could (and did) practice incessantly, for hours a day. And as the saying goes “Amateurs practice until they get it right. Professionals practice until they can’t get it wrong”.

For us, though, it’s a little trickier. We don’t really have the same scope for practising, experimenting, testing out different ways and approaches in a safe and private environment. We don’t have the practice room (for 98% of our time) and the concert hall (for the 2% of our time actually giving performances).

Sometimes when I mediate I can hear myself saying the same things as I said earlier that week, in another mediation, and the week before, and the week before that. At one level, that is fine. These interventions are generally effective and they have become an integral part of my practice over the years. Indeed, it’s partly why I get hired. But it’s also a challenge. A practice, however good, can easily become a rut. The limit of my vision can be reduced to what works. Or rather, what works for me.

Last Friday I had the great pleasure of having my good friend and distinguished Romanian mediator (and fellow Kluwer blogger) Adi Gavrila attend a mediation with me in London. He was there in an observer’s capacity, and naturally between meetings with either or both parties we talked together. It was quite clear that we had different perspectives on some aspects, and similar ones on others. It was also clear that we would not have mediated the same dispute in entirely the same way, though again there were significant areas of overlap. So what works for me is not the same as what works for others.

(I should add that for me it was it was a rich learning experience. Not the same as Casal’s practice room, but very rich. I commend it to you as a way of getting a different perspective on your practice).

So back to the question – how can we improve?

Often the most sustainable improvements are made gradually. The Japanese principle of “Kaizen” encapsulates this. The word means “continuous improvement”. It comes from the Japanese words 改 (“kai”) which means “change” or “to correct” and 善 (“zen”) which means “good”. It emerged in Japan after World War II as a management principle for improving industrial productivity, but now applies to every area of life. The key to it is to look continuously for small improvements, rather than occasionally for large ones.

Applying that to the practice of mediation, what possibilities emerge? Here are some suggestions.

• Take someone with you to a mediation (with the parties’ permission, of course). Not someone who is new to mediation, but someone with experience and with judgment you trust. Give them the brief of analysing what you do, and providing detailed feedback afterwards. If it is someone from another context (another country, another field of mediation, another profession), so much the better, as they are more likely to see things through different eyes. It is the challenge to our normality which is so useful.

• Do your own analysis after a mediation of what worked and what did not. I find this a challenge, simply because of the busy-ness of life and practice. But there are times when I know that I have been at the top of my game (regardless of whether a settlement has been achieved) and times when I know I have been less so. Capturing what has worked is important.

• Experiment a little. I don’t mean wholesale changes, not least because that is not fair or appropriate for clients. But doing a few little things differently can have a large overall impact. Sir Clive Woodward coached the English rugby team to World Cup victory against Australia in Sydney 2003 (sorry for reminding my Aussie friends!). Asked afterwards about how he had effected such an improvement in the team, he said “We tried to do 100 different things 1% better each”. It worked.

• Listen to wisdom from outside the mediator community. Don’t get me wrong – Mediator events are great, and I was hugely disappointed to have to miss the International Academy of Mediators meeting in California last week, a regular event from which I learn a lot from other mediators. But there is plenty of wisdom and insight outside our community as well. John Sturrock posted last week with some spiritual wisdom from a Franciscan monk, which was challenging and applicable to mediators.

So the next time you find yourself in a mediation, both doing and thinking in your rut, think about “Kaizen” and do something different. Who knows what you might learn? And if you do, please post it here!

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

Profile Navigator and Relationship Indicator

Access 17,000+ data-driven profiles of arbitrators, expert witnesses, and counsels, derived from Kluwer Arbitration's comprehensive collection of international cases and awards and appointment data of leading arbitral institutions, to uncover potential conflicts of interest.

Learn how Kluwer Arbitration can support you.