Armed with coloured paper, crayons and scissors, myself and nine other mediators spent a good portion of last Friday designing our “ideal” family conflict resolution service. While the background to this was, in part, recent and pending legislative change in the UK, some of which looks likely to impact negatively on families in conflict, these particular family mediators are not easily deterred, and our creativity was in full flow. For my part, I thought about the families I work with – all going through the process of separation, divorce or similar changes, but all different. I thought about the teenage son who, unable to cope with what was happening, dropped out of school and turned to drugs. To the husband whose decision-making was overshadowed by the fear he would not survive the cancer for which he was being treated. To the parents struggling to agree a parenting plan while fearing the implications of one parent’s on-going battle with depression. And, of course, to those many couples who are tied together, despite their efforts, by negative equity and inflexible mortgage companies.

You see where I’m going with this, of course. To effectively manage such situations we need more than just lawyers, or mediators, or therapists. Most professionals working with families, and even to a certain extent policy makers, would agree that there is no one suitable solution to, or intervention in family conflict that can be offered or made, nor can one profession meet all the needs of such families.

“They all come through one door” was the title of a talk given by the Chair of the Irish Legal Aid Board at the Annual Family Law Conference in Dublin in 2012 in which she set out the changing approach to family justice in Ireland. She spoke about the Dolphin House Mediation Project (which I have written about previously) a collaboration between the Courts Service the Legal Aid Board and the Family Mediation Service with the aim of diverting cases into mediation at the earliest opportunity. She also spoke about the need for integration with other services such as counselling, and the possibility of a separate family courthouse and courts system.

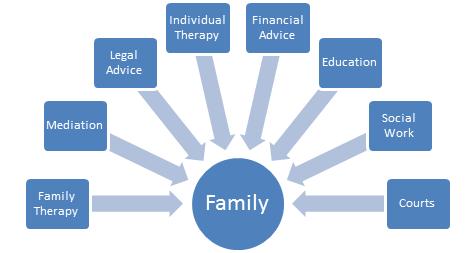

The idea of separating couples being able to come to one location where they can access lawyers, mediators, therapists and whatever other support they require, as in the figure below, ideally under one roof, or even through a well-functioning referral network appears seductively simple. Having a separate space where such services can be accessed would look very attractive to the parties and their children, and to the professionals involved, and could remove the pressure of conflicts being “resolved” on the steps of the courthouse, as they so often are (or aren’t).

The reality is, of course, always somewhat different. Even leaving aside all the logistical and practical issues around how to co-locate services like those above, particularly in smaller cities and towns, and the perennial question of how it would be funded, securing the buy in of the relevant professionals could prove more difficult than one would think. As a mediator in the private sector (though I am assured colleagues in the public service have similar experiences) my interaction with lawyers continues to be one of my main sources of stress. Many are unfamiliar with the mediation process, see it as a threat, or see it as something they should have no involvement in whatsoever. Often a solicitor won’t see the client until the mediation has finished, then pull the carefully mediated and crafted MoU to shreds and we have to start all over again. Or they are so enthusiastic about giving advice that the client can no longer see their own interests. Many clients will refuse to see a solicitor until mediation is finished in order to maintain control of the process and costs, which can have similar consequences. It can, of course, be just as challenging to have social workers or accountants involved in a process if they do not know enough about it. (And before everyone starts shouting, I’m sure lawyers, accountants and social workers feel just the same about mediators!) The point really is that if an integrated, multi-disciplinary model is to work, there must be co-operation, education of all involved and, most importantly, on-going communication.

The question of who, in each case, would “manage” the case, or be the primary contact for the clients, is also a tricky one. It would be a challenge for a mediator, for example, to take on such a role while maintaining impartiality and, most importantly, leaving the locus of control for the process with the parties. If it were a lawyer, whose lawyer would it be and how could one ensure that the conflict would be managed collaboratively and not go down the road so many separations do in this country.

Many challenges exist in implementing such a model but, as the Dolphin House Project in Dublin shoes, it is not impossible by any means. More achievable, and at least as important, is taking a more integrated approach to family dispute resolution from the point of view of the family itself. Relationship breakdown is rarely just about the couple – it has ramifications beyond them, the nuclear family, into the extended family and the community, nowhere more so than in Irish society.

How often are grandparents, for example, the casualties of relationship breakdown, no longer able to see cherished family members or grandchildren? What of the difficulties new partners or step-parents might have as family constellations change? Lisa Parkinson has written in detail about the benefits of taking an “Ecosystemic” approach to family mediation, which broadens the process to include and take into account the whole family and social system around a couple, not just the couple themselves. It is particularly valuable in the case of “blended” or second and third families, and in non-traditional situations where, for example, a grandparent or aunt plays a primary role in a child’s life. And then, of course, there are the children.

It is still rare to see children directly involved or consulted in family law proceedings or mediation in Ireland, despite many calls for change and the inclusion of provisions in the (still) draft Mediation Bill 2012 and the passing late last year of a Constitutional Amendment on children’s rights. I have had to divert to Germany to train in direct consultation with children in mediation, as training opportunities are so few and far between here. At this stage, there is plenty of research evidence supporting the inclusion of children, in an age appropriate way, in whatever process is used to manage family conflict and relationship breakdown.

Integration should not, therefore, be confined to services, but also to the users of such services. Wouldn’t it be great if my struggling families could go through mediation with appropriate and enlightened legal advice, avail of family therapy to manage the change, have the help of an accountant to figure out how to fund two households and all the while have emotional support in whatever way suits them best. I would hazard a guess that the outcomes, and ultimately, the costs to the parties, (emotionally and financially) and the State would be significantly reduced. Maybe we should just bring our coloured paper and glue into the policy makers, and set them to work on designing a family dispute resolution system. It isn’t really that complex. Except of course you’d need the Minister for Justice, the Minister for Children, the Legal Aid Board, the Family Mediation Service, the Family Support Agency and so on……and a lot of crayons…

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

Dear Sabine

Thank you for a highly topical piece about a critically important issue, particularly in Ireland where mediation is at a relatively early stage of its development. I can appreciate these problems as I have worn the hats of child protection officer, solicitor, barrister and now mediator and I agree it is a matter of communication and perhaps education. The legal profession need to understand the objectives and methodology of mediation, but at the same time the mediator needs to know the fundamentals of family law so that they don’t facilitate an agreement that is legally impossible or even legally problematic. This raises the hoary old issue about whether it is necessary for a mediator (as neutral facilitator) to have legal knowledge in order to be an effective mediator, the answer to which largely depends on the extent of intervention that the mediator employs when mediating. I think mediators need to have a workiing understanding of the law as this allows them to properly describe the choices available when the disputants outline their ‘wish lists’, but I know that a lot of people will disagree with me. It is a complex and perplexing issue. My service has assembled a team of like minded individuals including mediators, lawyers, an accountant / tax advisor, therapists, counsellors and psychologists, and finally academics to provide ongoing research, but this took a long time and a lot of energy. So far it seems to be working, but we always need to talk to each other, and constant meetings / consultations / training sessions are vital.

Best wishes

Neil van Dokkum

Arc Mediation, Waterford

http://www.arcmedlaw.com