There are times in mediation when emotions are so powerful that it’s impossible to think of anything else. This week I witnessed, at the very least, despair, fear, anger, hurt, sadness, care, love and relief. They can be fleeting – a flicker of amusement, a nod of recognition, a disdainful glance. Or they can be worn on the sleeve from start to finish, manifest as tears, a raised voice or over-anxious babbling.

Last month I listened as two senior employees rehearsed the same complaints against each other for a second meeting. One attacked; the other defended; the other attacked back, the first defended; and so on. But throughout the exchange my inner voice was saying: “Look at the way they’re sitting. These people don’t trust each other.” Eventually I gave in and voiced it: “I hope you don’t mind my saying this, but the atmosphere between you doesn’t seem very great.” Both immediately acknowledged it and, shortly after, one said to the other: “I’ll try to be less defensive.” This was accepted with great relief and some passion, and the course of the discussion changed.

I am not claiming any great or unusual insight. Mediators do this sort of thing all the time. But if you examine most of our models, our literature, and especially our public rhetoric, you see little talk of emotion. The overwhelming focus is on language, tactics and rationality, with an occasional nod to “body language”. By and large we speak as if we are mediating from the neck up.

Three years ago, in the Swiss village of Saas Fee, Michelle LeBaron and Carrie MacLeod brought together a group of mediators, academics and artists for a week enigmatically entitled “Dancing at the Crossroads”. I went with some trepidation. I think I expected to watch dancing: in fact we all danced, daily, for about 3 ½ hours, led by the extraordinary Canadian dancer, Margie Gillis. To my amazement it was highly enjoyable, but also intensely emotional. In the group discussions that followed I learned that others felt the same way. A consensus emerged that re-connecting with our bodies meant working and thinking in the emotional realm: a reminder that mediating from the neck up is simply impossible.

All of us left Saas Fee with a challenge: to write a chapter for an edited collection capturing the results of the week (Michelle LeBaron, Carrie MacLeod and Andrew Floyer Acland, The Choreography of Resolution: Conflict, Movement, and Neuroscience. Chicago: American Bar Association, 2013). My effort is entitled “Building Emotional Literacy: a Grid for Practitioners”, and I summarise it below. Recent mediations have only reinforced my conviction that we need to find effective ways to work with emotions.

On examining the vast literature on emotions, three things became clear:

1) the link between thought and feeling (or reason and emotion)

2) the importance of both positive and negative emotions in conflict resolution

3) the value of “emotional self-regulation” for our work.

The first point has been well explained by Antonio Damasio in the masterly “Descartes’ Error”. He makes a compelling case that rationality is impossible without effective emotional functioning: “Emotion and feeling, along with the covert physiological machinery underlying them, assist us with the daunting task of predicting an uncertain future and planning our actions accordingly” (Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reasons and the Human Brain. London: Vintage Books, 1994, p.xxiii). This runs counter to the background assumptions of many of the professions from which mediators are drawn: ““Negotiators – especially those trained in law – commonly … [try] to exclude emotions from negotiation and to focus solely on so-called objective, rational factors, such as money” (Leonard Riskin, “Further Beyond Reason: Emotions, the Core Concerns and Mindfulness in Negotiation” Nevada Law Journal, vol. 10, no.2, Spring 2010, 290-337, p.294).

Second, while most of us associate conflict with negative emotions – anger, frustration, fear, sadness and confusion – we tend to underestimate the importance of positive emotions in its resolution. Cloke names “forgiveness, open-heartedness, empathy, insight, intuition, learning, wisdom, and willingness to change” (Kenneth Cloke (2009) “Bringing Oxytocin Into the Room” www.mediate.com/articles/cloke8.cfm note 46, p.1).

Third, the capacity to regulate our emotions has been described as the “master aptitude” (Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. London: Bloomsbury, 1995 pp.78-95). It seems to come down to two principal strategies: suppression and reappraisal. While suppression is socially useful, reappraisal is more far-reaching, enabling people to tell themselves a different story and thus experience a different emotion. Mediation looks as if it operates in part by assisting with this task.

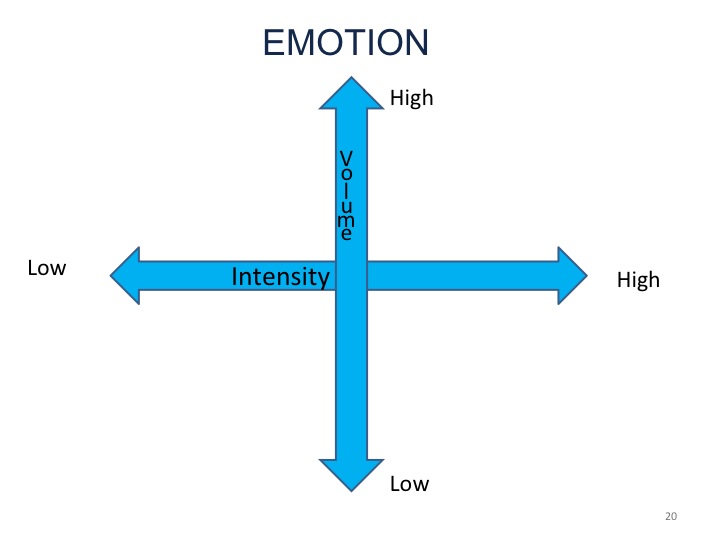

I may be guilty of setting up a straw man: the mediator who ignores emotion or is complicit in its suppression. But even if we acknowledge the significance and sheer power of emotions in our work, we receive little guidance from our professional bodies and texts on what to do with what we observe. So I want to share a simple device, the “emotion grid” (Charlie Irvine, “Building Emotional Intelligence: a Grid for Practitioners” in LeBaron et al, 2013, p.107). It attempts to provide a graphic display of the emotional action in a room by means of a simple insight that emerged at Saas Fee: the volume (or outward display) of an emotion is not necessarily related to its intensity (or inner force). The grid has two axes, below:

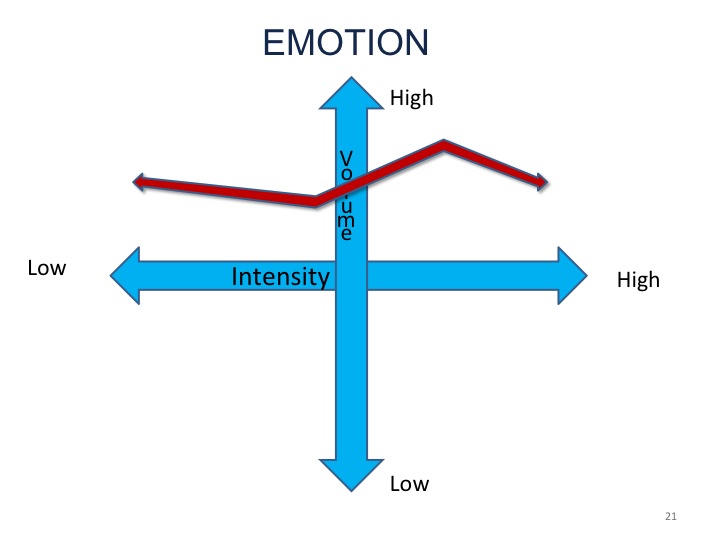

To illustrate how it might work, imagine an emotion at the top left end of the grid. I bang my toe. I shout out, loudly, holding my foot and jumping about. The volume is high, but the intensity not, and it passes in seconds.

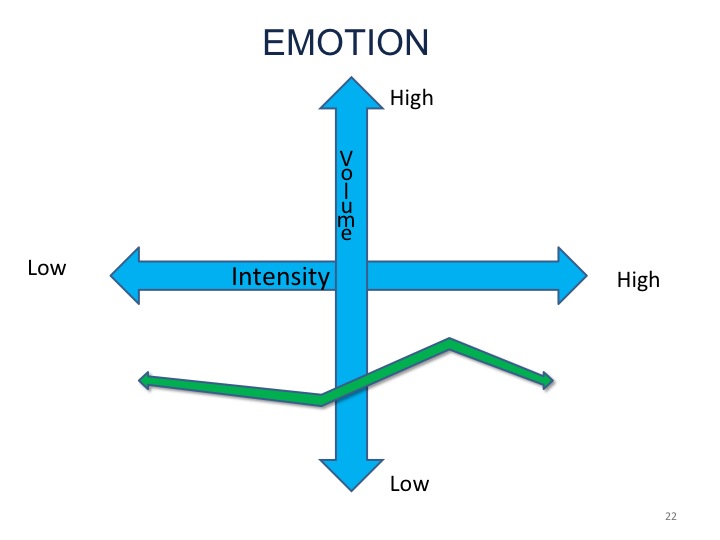

Moving to the bottom right, a low volume/high intensity emotion could be grief, held back but internally overpowering, affecting both thoughts and actions. Then at the top right we have high volume/high intensity – on one memorable occasion a client drew her head back and emitted a high, penetrating scream. I (and all the neighbours) could hardly mistake the strength of her feelings. And finally, bottom left, we have a resting state – low volume/low intensity.

We could use the grid to calibrate our own and other people’s cultural preferences. For example, some clients may express all emotions volubly, whether intense or mild, as below:

Others may live at the quiet end of the scale:

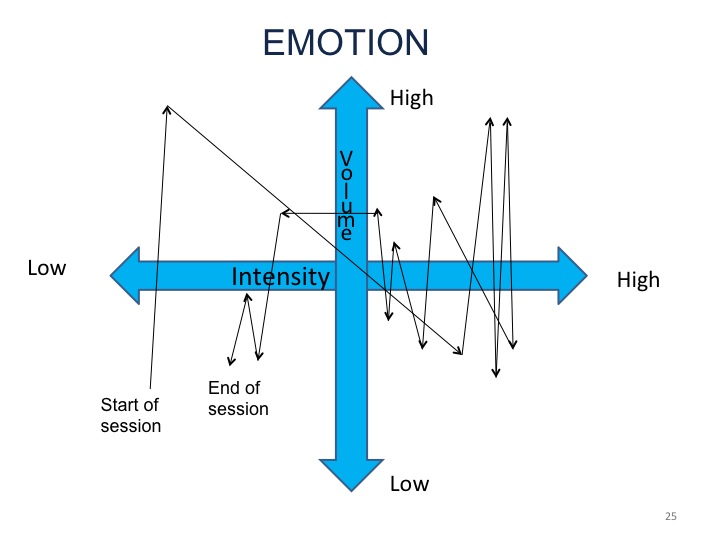

My hope with the grid is to provide a way for mediators to conceptualise their own emotions as well as those of their clients. In a typical mediation we may feel that the emotional action goes like this:

Plotting our emotions will allow us to begin to recognise what we are feeling and how we are showing it, the first step in emotional self-regulation. We can compare one mediation to another, perhaps using colours to trace our observations of each client’s volume (and guesses about their intensity) and a separate colour to plot our own responses (about which we have more accurate knowledge). We can compare our emotional range with colleagues, perhaps discovering that our taken-for-granted response to a particular display of feelings is not the only possibility.

Implicit in all of this is a simple assumption: that we are capable of seeing and interpreting the emotional action in a room. Following Damasio and others, this capacity involves a seamless calibration of thought and feeling, using visual, auditory and other information. We see what’s going on. We hear the tone of voice. We feel the atmosphere. My hope is that in future we will have a range of responses that goes beyond simply speaking. Dancing at Saas Fee reminded us that our bodies are at the table too. Years ago, someone told me that in mediation: “You are your own instrument.” If that instrument is important in reading the emotions in the room, then it makes sense to calibrate it, and my hope is that the grid will provide a way of doing so.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

Analyzing the body language of the parties is essential as

it may be an indication of how a session is going. While it is important (and even necessary) for the parties to release some steam, it should not get in the way of the resolution process itself and break the communication between them. Furthermore, it is also fundamental for the mediator to be

very aware of “his own” body language. Remaining calm and adopting positive postures all along the session is also part of the resolution process.