This post was prepared by Christian Radu Chereji and Constantin Adi Gavrilă.

There is one thing that strikes every researcher when confronted with EU/national legislation regarding mediation: when one reads the arguments of any piece of legislation, everything looks great. The powerful motives are formulated with excellent logic; but there is no follow-up, no monitoring mechanisms provided in most cases, no attention to effects whatsoever. It’s like the law makers think that just enacting a piece of legislation constitutes in itself the resolution of the problems tackled.

This was specifically the case of Romania who has been struggling for almost twenty years to implement appropriate courses of action for a sustainable development of mediation. As many other EU countries, Romania learned the hard way that new mediation legislation is simply not enough to create a reality. It can be quite the opposite at times – inefficient legislation can lead to even worse situations than no legislation.

The mediation law adopted in 2006 by the Romanian Parliament has been modified for more than fifteen times, each modification tentatively solving one problem and creating ten others. Unfortunately, because there are no monitoring mechanisms and hence statistics available, there is still no clarity with respect to use of mediation and its impacts on the judiciary. We simply don’t have evidence regarding the impacts of mediation on both the private and the public sectors. What we do have, is an anecdotal belief that the mediation experiment has “successfully” failed in Romania.

Given all the above, the Propact Center for Mediation and Arbitration has implemented, between June 2018 and October 2019, the project “Mediation – effective public policy in the civic dialogue”. The project was financed under the Romanian Operational Program Administrative Capacity 2014-2020, Priority Axis 1 – Public administration and efficient judicial system, Component 1 – “Increasing the capacity of NGOs and social partners to formulate alternative public policies”. The overall goal of this project was to formulate, most likely for the first time, a sustainable public policy regarding mediation in Romania.

We’re not going to spend a lot of time here describing the mediation status in the EU or the Romanian context. What we will say, however, is that after developing a safe full voluntary mediation legal framework for almost 10 years and some 20+ thousands mediators trained a “chance” was taken to boost the demand for mediation through an information session mandatory but free of charge for the plaintiff, before submitting the case to the national courts that, otherwise, would dismiss the case as inadmissible.

Although the strategy of developing the demand for mediation through legislation (i.e. the opt-out model implemented in Italy) is a very good one if combined with effective policies to ensure the quality of mediation services, to promote and use mediation services by both the public and private sectors, this strategy can actually make things a lot worse, which was the case of Romania. Specifically, the Romanian Constitutional Court decided in 2014 that the INADMISSIBILITY SANCTION for failure to attend the mandatory information sessions is not aligned with the letter of the Constitution. Following this constitutionality check, the perception in the public space was that MEDIATION is not constitutional.

Hence the above-mentioned project was an excellent opportunity to take a step back, return to the drawing board and perhaps think through what can governments to “zoom out” from the legislation component and look at the larger picture, set up realistic goals and adopt courses of action – yes, including enacting legislation.

Situational Analysis

An initial assessment process included both qualitative and quantitative research. As qualitative research, individual interviews, focus groups and roundtables proved to be instrumental for the understanding of underlying views, opinions, and motivations related to mediation. The consultations with experts uncovered trends in thought and opinions, and dived deeper into concerns of both sides of mediation, demand and supply. For the quantitative research, two very well thought and extensive surveys were made available online (available in Romanian here), one for mediators and the second one for other stakeholders. The second survey was available for members of a trade union organizations, civil servants, entrepreneurs or employees in the private sector, lawyers, other professionals (other than the lawyers), judges and prosecutors, policeman, members of the Parliament, university and pre-university professors, members of consumer protection associations and citizens. Both questionnaires were structured to include information about (1) the quality of the mediation service, (2) the capacity to provide mediation services, (3) the legal framework for mediation, (4) trust levels in mediation and mediators, (5) relationship systems for the mediators, (6) use of mediation services, (7) regulation system and management of mediation, (8) mediation financial sustainability, and (9) synchronization of the Romanian mediation system with international good practices. The survey is still open, as it provides a very useful consultation tool with real time available results and advanced filtering accessible for both mediators and other stakeholders. The filtering information include the date when the survey was submitted, location, age, gender, education, self-assessed experience with mediation and other specific to each survey such as the accreditation interval for mediators of the type of stakeholder for other stakeholders. Again, the consultation approach was focused on not only (or mainly) mediators, but to others that may influence or may be influenced by the implementation of mediation in a jurisdiction.

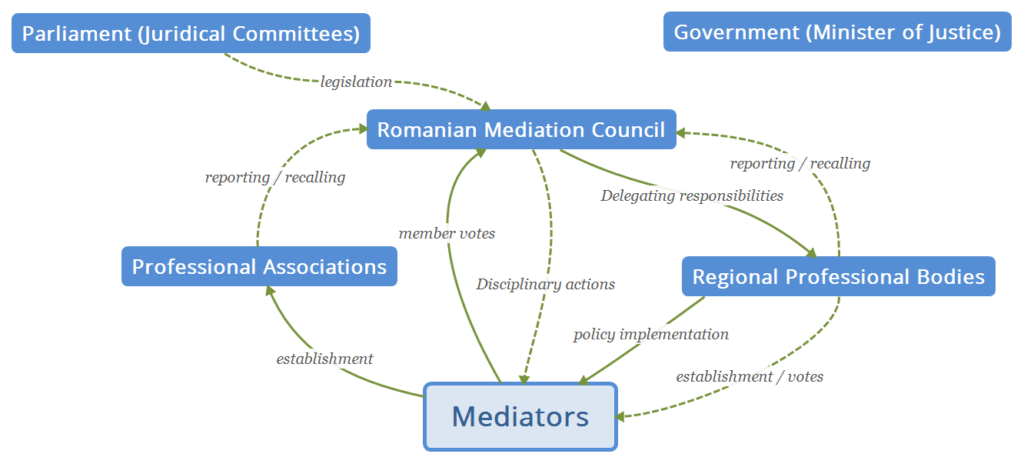

The system is organized with the following main institutions – the Mediation Council, the mediator‘ associations, the mediators.

The analysis observed the following functions of the mediation system: management, representation, regulation, use/quality and monitoring. We argue that the implementation of all these functions is faulty because the lack of financial and professional capacity of the Mediation Council and of the mediator organizations, lack of accountability of the Mediation Council or because of lack of attributions and motivation for the Romanian Government.

The entire mediation system has no access to public funding. The law has left the funding of the entire mediation implementation and marketing on the shoulders of the mediators themselves. This has created a vicious circle: mediation marketing has to be funded from revenues made by mediators which cannot make them without the vital marketing. Briefly, no marketing, no clients; no clients, no revenue; no revenue, no resources for marketing. Therefore, the mediation providers don’t have the financial capacity to make investments that will maintain their competitivity in the market. Further, the mediator associations have difficulties in collecting member fees, therefore their very limited capacity to promote mediation, and the quality of their mediators. Hence, the trend is for mediators to leave panels and start new professional endeavours. Only 4000 mediators are to date (November 2019) on the national panel that included at some point as many as 12000 mediators. While the main funding source for the Mediation Council consisted in accreditation fees from mediators, trainers and mediation training providers, this trend prompted the Mediation Council to impose annual fees to mediators although these fees were never mentioned in the law and then to sue the mediators that didn’t pay that fee (a name search “CONSILIUL DE MEDIERE” – Mediation Council in Romanian – on the national portal of the courts http://portal.just.ro/SitePages/dosare.aspx reveals almost 1000 lawsuits where the Mediation Council is a party, in cases mostly related to the “annual professional fee”).

Designing options

The main goal of the project being the formulation of an alternative public policy to the present situation, our group took the mandatory first step of designing the possible optional courses of action that could be taken. Given the theoretical tenets of public policy design, it is clear that we are considering the “analytical approach” to public policy design, in contrast with the “political approach” (Dye, 2016). Whether this later approach refers to building and mobilizing the political support needed to adopt and implement a certain public policy, the former concerns the rational process of identifying feasible options and choosing the one that offers the most benefits for the predicted costs, and the one that comes closest to the overall goals formulated at the beginning of the process. This post provides a glimpse into the “analytical approach” that our team has taken; the “political approach” falls far beyond our scope here, but it is our team’s major concern for the near future, because these two approaches are the two sides of a single coin – and there is no coin in our known universe that can exist having only one side. Specialized literature all point to the fact that, even if for academic and research reasons, we can talk of two different approaches to public policy design, in reality there is practically no way to separate one from each other. No policymaker is going to select a course of action that clearly cannot muster any support whatsoever, no matter how reasonable it seems for the moment; all the same, no policymaker is going to take the first course of action presented to them without considering at least a number of other options before making a decision.

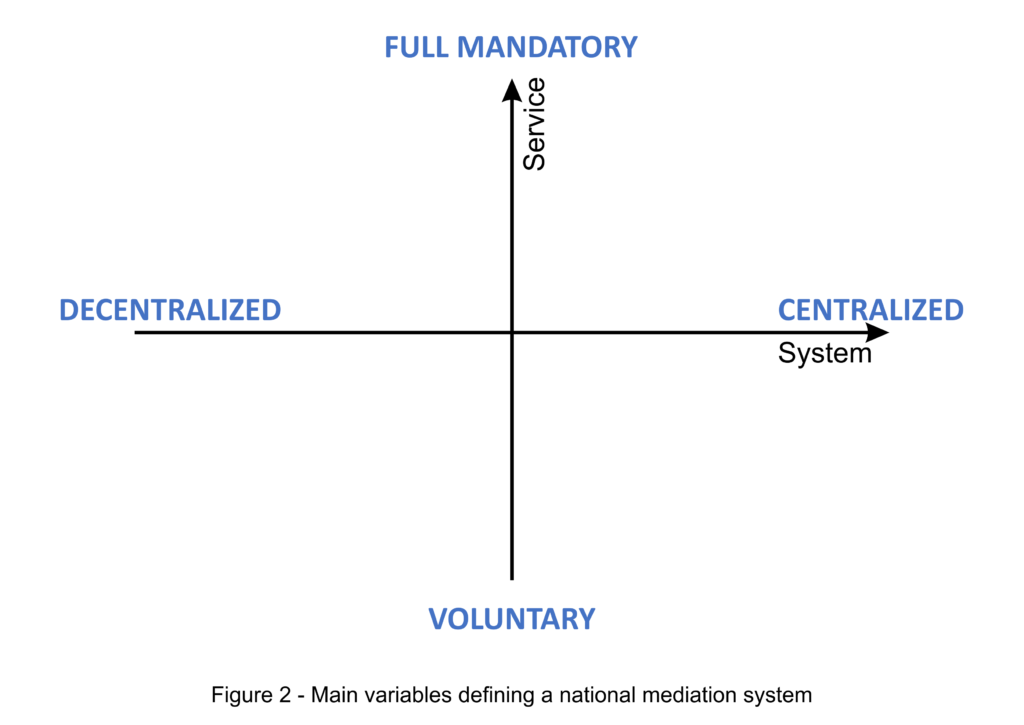

With these conceptual considerations in mind and with the major goals already formulated, our team strove to identify the potential options to the current situation. Given our intention of pursuing a systematic approach to this end, we became aware of the need to find out what are the main variables defining a national mediation system, those variables that we can find at the core of any mediation system in the world, regardless of culture, legal system, justice system, political and social environment etc. Looking at our own prior situational analysis, we came up with a pair of variables that, we reckon, define any mediation system:

1. the system organization variable, ranging from completely centralized (all mediators basically being part of one, single, nation-wide organization, with all the decision-making power resting with the central bodies of this organization – the pyramidal structure; as an example, the Maltese national mediation system) to totally de-centralized (mediators belonging to a number of professional organizations, of various characteristics and pursuing a range of goals, with no national central decision-making body – the network structure; as an example, the English and Wales mediation system, if such thing really exists), and

2. the mediation service providing variable, ranging from purely voluntary (mediation used only upon the free will of the parties, with no coercion whatsoever formulated by the law or public authorities – as it was the case in Romania and many other EU countries at the very beginning) to full mandatory (where mediation is mandated by the law and enforced by the courts with penalties for non-compliance, for all cases with very few exception and with no opt-out – this extreme situation cannot be found in practice anywhere in the world at present date, but can be intellectually conceived).

If we use these pair of variables as a system of two perpendicular axis, we end up with the following graphic:

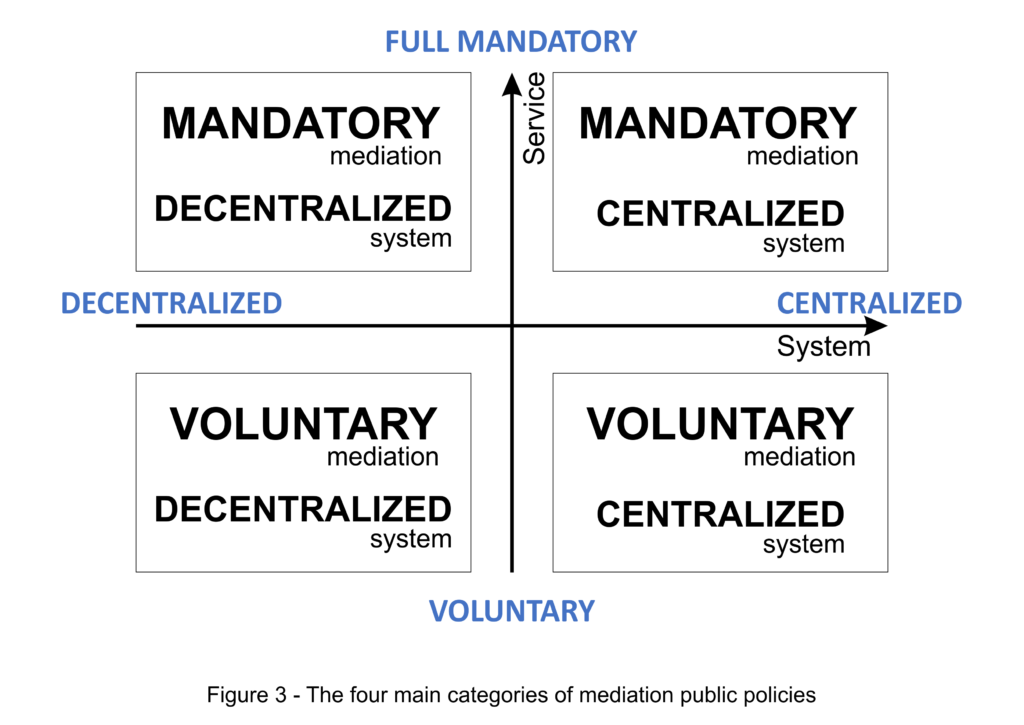

Following the building of the matrix and the identification of the four distinct categories, we proceeded to put meat on the bones of this structural skeleton, by devising all the components of each ideal-type system corresponding to those categories. Basically, we imagined how these ideal-type systems would look like from the point of view of the two main variables – organization and functionality – and then we projected what kind of regulation modifications were to be done to give it legal form; what would the funding look like and estimated the costs of implementation; and what impact all of these would have on the marketing, stimulation and enforcement of mediation utilization. At the end of each exercise we did a simple SWOT analysis to see how the benefits of each ideal-type system would be compared to the estimated costs and how they align with our overall goals. It has to be noted here that we imagined our ideal-type systems as located in the extreme points of each axis, but we devised the component parts of each variant using the ingredients of the Romanian national mediation system, as it exists today.

Regardless, we consider that our approach can be used by anyone all over Europe and the world, as the structural elements remain the same across cultures and legal systems; what changes are the components – institutions, organizations, courts and structure of the justice system etc. – and the way they are correlated one to each other depending on national specifics.

With the four options defined and structured, we then proceeded to identify a fifth option, a so called “middle ground” option – one that would be a combination of the best parts of each of the four ideal-types according to the results of our SWOT analysis combined. There were also two other conditions (besides the overall goals) for building the fifth option, in relation to the “political approach” of public policy design we have noted above – there were to be a minimum possible of legislation modification, as the Romanian government branches already suffer from a “mediation regulation modification traumatic fed-up syndrome”; and, second, that we were looking at the improvement of the current situation and system, not the complete overhaul of them, such an endeavour having almost no chances of gathering relevant political and professional support.

We decided to go for a fifth “middle ground” option as a “do nothing” course of action – the regular last option that we can find in any rational actor model decision-making process description from Graham T. Allison (Allison, 1971) onwards – was considered a no-go by our team from the beginning, for reasons already described here before.

In building the “middle ground” option we started with another SWOT analysis, this time of the current mediation system present in Romania at date. Our intention was to find out what parts or components of the current system were not working, to identify their causes and then use the results of the SWOT analysis of the four ideal-type variants to generate replacements for those unfit or missing parts.

The result was a set piece of public policy paper containing clear recommendations for our policymakers regarding the necessary steps to be taken in order to improve the current system and make mediation one of the mainstream methods of dispute resolution in Romania. We are not going to get into details as the time is short/space is limited and because the recommendations are specific to the Romanian particular situation. We will include all the aspects regarding the structuring of the four ideal-type systems and of the “middle ground” option in a future publication of larger format.

Further developments

One of the biggest challenges for the researcher of mediation systems across the world, with an emphasis on EU, is the current lack of systematic data gathering at national/EU level regarding all aspects concerning mediation – number of mediation cases per year, number of accredited mediators, types of cases most solved through mediation, proportion of cases referred to/solved through mediation, types of cases most likely to be referred to and solved using mediation, costs of mediation (compared to costs of litigation), degree of users’ satisfaction with mediation and mediators and so on. There has been constant talk about “mediation not-working” or “mediation failure” at national and EU level, with studies trying to identify the reasons and the possible remedies; all this talk is in vain if not based on solid data backing the arguments. Simply asking mediators in any given EU member state to evaluate the number of cases mediated per year is definitely not acceptable as data gathering, not to the current standards in social research. And policies based on hunches and educated guesses have limits that are obvious today.

It is one of our major recommendations for policymakers at national and EU level: design and implement a valid, reliable, consistent and systematic data gathering mechanism regarding the proceedings of mediation. Without such a mechanism, all debate over the future of mediation remains pinned on anecdote, hope and particular examples that nobody can prove they can be successfully replicated in other places and cultures. A sound mediation public policy has to be based on solid data that can illuminate feasible paths of action and bring relevant arguments for their implementation.

In many countries, mediation implementation has been done by paying attention only to the overall goals formulated by initiators – looking for a more collaborative, non-confrontational method of dispute resolution, reducing courts backlogs, building a more harmonious society etc. – with little or no focus on the way this implementation could impact the lives and interests of various stakeholders. Introducing mediation represented everywhere in America and Europe a change; and every change has winners and losers, people that win by having that change implemented, and people that might lose. No attention was given to potential losers, as policymakers were taken aboard of the “mediation miraculous remedy” ideology promoted by supporters. But reality proved the contrary. Some people have been negatively affected and mediation has not been even by far the panacea for dispute resolution. A balanced, moderate approach is needed and there is an obvious requirement that all stakeholders have to be engaged in the process of mediation public policy building. The political approach of public policy design, no matter how unpalatable to many activists working for the promotion of mediation, cannot be discarded. The designers have to drag the buttons on each of the two scales – organization and functionality – until a course of action is found that can not only satisfy the overall goals of mediation public policy design process, but can mobilize the widest support among potential stakeholders and the public at large. No matter how clever and effective a course of action looks on analysis, it is equal to zero if there is little of no support for it. It will fail the reality test, as many mediation implementation strategies have done along the time.

In the end, a word of caution regarding the indiscriminate transfer of models from one country to another. There is huge fashion today of looking over the fence to the neighbours’ strategies and policies for inspiration. Whether such an exercise has its uses in terms of learning from the mistakes made by others, the public policy designers should refrain from too liberally emulating “successful” model, policies that allegedly work miracles elsewhere and are presented by interested parties as “the” way forward. Given the present lack of systematic data regarding how mediation works and why it works (or not) in EU member states, all these pro domo pleas should be taken with caution. Design of public policies should begin with a thorough, comprehensive needs assessment analysis; a clear formulation of overall goals, directly related to the society, culture and government of implementation location (not goals taken from other countries as part of a vogue); a systematic approach to identification and structuring of optional paths of action; an solid analysis of the benefits and costs of each path; a choice of the path that not only presents the most attractive cost-benefit ratio and comes closest to the overall goals, but also has the support of the a substantive majority of potential stakeholders and of the public at large. Of course, such a process is time- and resource- consuming, which might make it difficult to digest by policymakers usually with an eye on the next elections, but it has obvious benefits, one over all others: it might actually work. Going the easiest path, by transferring into one country’s legislation the basic tenets of a so-called successful model, un-critically and with no attention given to country particularities, costs, support and marketing, might give some policymakers the benefit of having something to show the constituents for the money spent and it might even have some short-term results. However, in the long term, that strategy is not going to work. Low-hanging fruits are rarely the best.

Conclusions

Unfortunately for mediation and mediators, there has been nowhere in the world a systematic approach to design mediation public policies seriously contemplated along the time. Without going too far back in time and too deep into the argument, we cannot point to any place in the world where implementation of mediation into the national justice systems has been the result of a full-fledged public policy, as defined by domain literature. Leaving aside the un-necessary academic hair-splitting attention to details and retaining only the great picture, we couldn’t identify a mediation public policy fully articulated and implemented with consistency. Mainly, mediation implementation was a matter of deciding that an alternative to courts is necessary, of deciding that mediation can be a solution and then producing legislation with the goal of inserting mediation among the recognized methods of dispute resolution. Little attention has been given to how that particular legislation was to be integrated within the larger corpus of national laws and, especially, courts’ procedures, little attention was given to funding requirements and almost no attention to marketing and enforcement. Mediation implementation has been, almost everywhere, done piecemeal, one measure today, another tomorrow, it has been victim of changes of government and government priorities, funding cuts, abrupt changes in approaches and, most of all, victim of opposition from entrenched interests coming from stakeholders insufficiently informed or co-opted in the decision-making and public policy design. As a result, mediation systems today look like a lodge in the woods, built over time from different materials and furnished with bits of old furniture left over after various renovations of the main residence – a hotchpotch of non-matching parts, hardly the encouraging great picture that a mediation system needs to be successful.

The major benefit of our approach was that it first stipulated what the main goals were; secondly, it identified the two major variables that define any mediation system, wherever it may be; thirdly, that it structured the four ideal-types of mediation systems and described them in detail, regarding organization, functionality, legislation, marketing, stimulation and enforcement; fourth, that it analysed all of these four types in terms of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, allowing the policy designers to use the scales of centralization-de-centralization and mandatory-voluntary to fine-tune their option; fifth, that is designed a method of upgrading/improving the current mediation system using the results of the ideal-type systems SWOT analysis to replace the dis-functional parts and add or delete parts that missing or, respectively, un-necessary. The end result is a public policy paper that can map the road that has to be taken by policymakers and stakeholders to bring the system up to expectations and offer mediation as a mainstream method of dispute resolution.

List of bibliographical references

Allison, Graham T., Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1st edition, Little Brown, 1971

Dye, Thomas, Understanding Public Policy, Pearson, 2016, 15th edition

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.