I’ve mentioned the use of Decision Trees by mediators previously on this blog. Here and here and here and here. So why do I keep banging on about them? Well, first, because I believe they are such an indispensable tool in the commercial mediator’s toolkit. But the reason I thought it appropriate to return to this topic now is because of my recent discovery of a website that greatly simplifies constructing a decision tree, on the fly, for most mediated cases.

SilverDecisions provides free and open-source decision tree software and I am finding I can make use of it in virtually every mediation. Let me illustrate my use of the site by referring to a recent mediation. Names and amounts have been altered in the interest of confidentiality.

The case involved a wrongful dismissal claim by a long-time employee of a large corporation. The Plaintiff claimed to have been wrongfully terminated and entitled to 24 months notice plus an additional $100,000 (all figures CAD$) in punitive and aggravated damages. The total value of all claims was about $400,000. The Defendant employer claimed that the employment contract had been “frustrated” due to the Plaintiff having been away from work for an extended time due to a disability. If the Court ultimately agreed the Defendant would only be ordered to pay the statutory minimums for the Province of Ontario, about $71,000.

Stated simply, a decision tree is a tool used to value the financial outcomes possible in any litigation. It does not measure the value of intangibles such as stress, anxiety, and uncertainty.

A decision tree analysis involves four basic steps:

-

- Listing the various possible events which might occur in the course of litigation (or beyond);

- Considering the costs or gains associated with each possibility;

- Discounting each possibility by its probability-estimated likelihood that it will occur; and

- Evaluating the overall picture by multiplying each possibility by its probability.

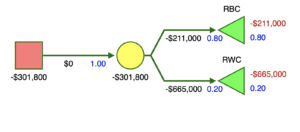

There will be a different decision tree analysis for each party to a lawsuit. For the purpose of my analysis in this very simple case, I boiled the possible litigated outcomes down to two: a reasonable best case and a reasonable worst case. From the Defendant’s perspective I then “guestimated” those outcomes as follows:

Reasonable Worst Case (Defence Perspective)

- Award against: -$400,000

- Cost Award against: -$75,000

- Defendant’s Actual Costs: – $160,000

- Defendant’s Lost Productivity: -$30,000

- Net Cost of Reasonable Worst Case: -$665,000

Reasonable Best Case (Defence Perspective)

- Award Against: – $71,000

- Cost Award in Favour: $50,000

- Defendant’s Actual Costs: – $160,000

- Defendant’s Lost Productivity: -$30,000

- Net Cost of Reasonable Best Case: -$211,000

At the Defendant’s request, I assigned a probability of 80% to their best case. This resulted in the following SilverDecisions tree.

On these assumptions, the Defendant should be indifferent between setting the case for about $300,000 and proceeding with the litigation.

On these assumptions, the Defendant should be indifferent between setting the case for about $300,000 and proceeding with the litigation.

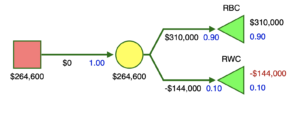

Now, let’s turn to the Plaintiff perspective. The calculations are a little different.

Reasonable Best Case (Plaintiff Perspective)

- Award: $400,000

- Cost Award: $75,000

- Plaintiff’s Actual Costs: -$160,000

- Plaintiff’s Lost Productivity: -$5,000

- Net Value of Reasonable Best Case: $310,000

Reasonable Worst Case (Plaintiff Perspective)

- Award: $71,000

- Cost Award against: -$50,000

- Plaintiff’s Actual Costs: – $160,000

- Plaintiff’s Lost Productivity: -$5,000

- Net Cost of Reasonable Worst Case: -$144,000

The Plaintiff insisted that he had a 90% probability of achieving the best outcome. The SilverDecision tree looked like this.

On these assumptions, the Plaintiff should be indifferent between setting the case for $264,000 and proceeding with the litigation.

It will be noted that even with diametrically opposite views on the likelihood of success there is still a $37,200 zone of possible agreement. It will also be noted that in Ontario, a loser pays costs jurisdiction, costs have a significant impact on the analysis. In the Defendant’s best case I assumed that they would serve an early Rule 49 offer to settle and that costs would flow in their direction were they successful at a trial.

Another aspect of costs relates to legal fees and disbursements incurred to date. Subject to the retainer arrangements those are generally “sunk costs” and not taken into account in building the decision tree.

Let me stress that this is the simplest of decision trees. More complex trees would build in the outcome of preliminary motions for summary judgment or the possibility of appeal of an adverse decision. There could also be a range of damages considered (high, mid and low) with different probabilities attached to each. A good discussion of more complex decision trees can be found here.

All of that can be easily accommodated at the SilverDecision site. It can be a powerful exercise to actually construct the decision tree on the website in real-time on your laptop or tablet with the input of the client and lawyer in a caucus session.

So what happened in the case I described. Well, we’re still talking. Mediators know that it is often hard for parties (and their lawyers) to come face to face with the logical consequences of their own predictions. Whatever happens, though, I have no doubt that the decision tree exercise and the use of SilverDecisions will help everyone involved make better decisions, all things considered.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

great work , well done thanks

When I first came across this online, I didn’t anticipate that the post’s material would be so deep that I would end up spreading the link to such a large audience. With every single line, the writer has managed to unravel some interesting concepts about data science that I never knew existed. This post motivated me to read more on this subject, and I am forever thankful to the writer for introducing me to a new world through this post.

best data science course in hyderabad with placement