This series of blog posts explores investment mediation from a variety of angles. In part one, we explore how to determine whether—and when—mediation is an appropriate option for resolving an investment dispute. Part two elaborates on what mediation is—and how it works—in the context of investment disputes. Part three outlines the primary differences between mediation and conciliation at ICSID.

Interest in investment mediation has grown in recent years. ICSID has developed a set of Mediation Rules specifically tailored for investment disputes, and supported the development of investment mediation through a number of other contributions, including most recently the Background Paper on Investment Mediation and an Analysis of Investment Treaty Provisions on Mediation.

In practice, questions often arise as to when mediation is a suitable option for resolving a particular dispute. Are there certain types of investment disputes that are more, or less, amenable to mediation? And are there particular stages in a dispute when mediation is a particularly effective intervention?

The short answer to these questions remains, as is often the case in addressing complex issues, it depends. It depends in particular on the parties, their relationship, the parties’ goals and how much control the parties wish to retain over the dispute settlement process and its outcome.

What is investment mediation?

To determine whether a particular investment dispute is suitable to be resolved by mediation, it is helpful to start with a clear understanding of what mediation is. Adopting definitions from the OECD, the World Bank Group and others, mediation is a flexible process in which an independent and impartial person actively assists the parties in working towards a negotiated agreement to resolve a dispute or difference, with the parties in ultimate control of both the decision to settle and the terms of resolution. Investment mediation can be understood as a mediation that relates to an investment and involves a State, a State entity or a Regional Economic Integration Organization (REIO). Indeed, this understanding is reflected in ICSID’s proposed Mediation Rule 2(1). Mediation requires the parties’ consent. This can be based on a contractual provision, be agreed ad hoc between the disputing parties, or based on the State’s standing offer to mediate in an investment treaty.

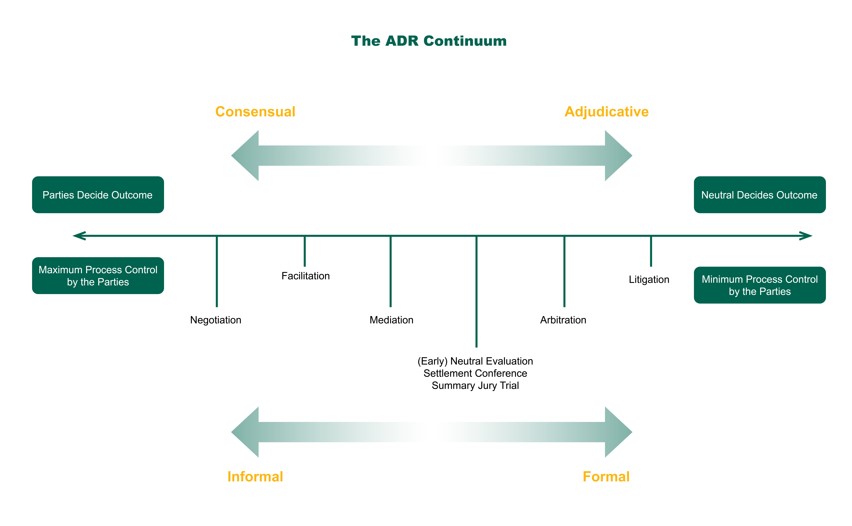

Looking at the simplified spectrum of dispute resolution options, often described as the ‘ADR Continuum’, it is clear that parties retain more control over the process and outcome of a mediation than, for example, an arbitration.

Is mediation suitable for an investment dispute? What are factors to be considered?

Experience has shown that investment disputes of all types can be resolved by a negotiated solution—indeed, roughly a third of all ICSID arbitration cases are settled or discontinued before reaching a ruling by a tribunal. Parties have reached agreed solutions in disputes over measures of the executive branch (revoking a concession), disputes over measures enacted by a legislature (adopting a new law that is alleged to breach the State’s international treaty obligations), or disputes arising from acts or omissions of the judiciary.

Considerations that parties may wish to consider when assessing whether to mediate an ISDS dispute are the following:

– Willingness to engage in negotiations. First and foremost, given that mediation is in essence a facilitated negotiation between the disputing parties, disputing parties need to assess whether they wish to engage in negotiations to find a mutually acceptable solution. This may be less likely where deep distrust exists between the parties. It may be more likely if there is a desire to continue the relationship with the other disputing party over the long term; for example, to retain or expand a particular investment, or because the investor has a number of investments in a host country and wants to avoid one investment dispute jeopardizing the entire portfolio. However, even if there is no desire to maintain a long-term relationship, there may be an interest in settling the dispute amicably through mediation. This may be because of perceived time savings, or because of benefits that derive from the parties’ ability to design the settlement agreement themselves.

– Comprehensive assessment of the dispute. Determining whether mediation is a suitable process requires a comprehensive assessment of the dispute and the disputing parties. There might be parts of a dispute that are more suited for an amicable process and a negotiated solution than others.

– Analysis of the stakeholders in relation to the dispute and stakeholders relevant for a possible solution. In some disputes, multiple parties with differing interests are involved—either on the side of the state or on the side of the investor. For example, the entities who were involved in the circumstances leading to the dispute may not necessarily be the same as those relevant for or involved in finding a negotiated resolution. A careful dispute and stakeholder analysis will help disputing parties identify for which parts of a dispute, or with which parties or entities, a facilitated negotiation may be most effective.

– Desired structure/design/form of the dispute resolution process. When determining the suitability of mediation as a form of facilitated negotiation, parties may wish to assess the characteristics of the process they want to use. Parties may prefer a formal framework with specific rules and powers—such as those pertaining to evidence or the ability to order interim relief—in which case arbitration or litigation may be more suitable. That said, investment mediations are generally more formal than commercial mediation, and process rules do exist (see for example the Mediation Protocol in MR 20). However, the mediator has no powers to issue orders or provide for interim relief.

– Desire to maintain control of the outcome. Disputing parties should also consider whether they wish to keep control over the potential resolution, as well as determine what an agreed outcome could look like. This may include tailor-made solutions that involve aspects other than the pecuniary relief typically available under most legal instruments. Alternatively, should the parties prefer to delegate the resolution to a third party to issue a final and binding ruling, an amicable dispute resolution process such as mediation may not be suitable.

– Financial resources to cover the costs of the dispute resolution process. When assessing which dispute resolution process to choose, parties may also consider the relative costs of pursuing arbitral or amicable processes, taking into account also the amount in dispute (i.e., likely to be recovered in an arbitral process). Based on the information available on investment mediations, the cost of investment mediation appears to range between 25,000 and 200,000 USD.

– Desired time frame to resolve the dispute. Finally, parties may also wish to weigh dispute resolution processes in terms of their anticipated duration. For some disputes, a rapid resolution may be of utmost importance. Known investment mediations that concluded with an agreed solution lasted on average between 6 and 9 months, counted from the appointment of the mediator.

Parties may wish to consider these aspects at different stages of the dispute—or the chosen dispute settlement process—as their assessment may change over time.

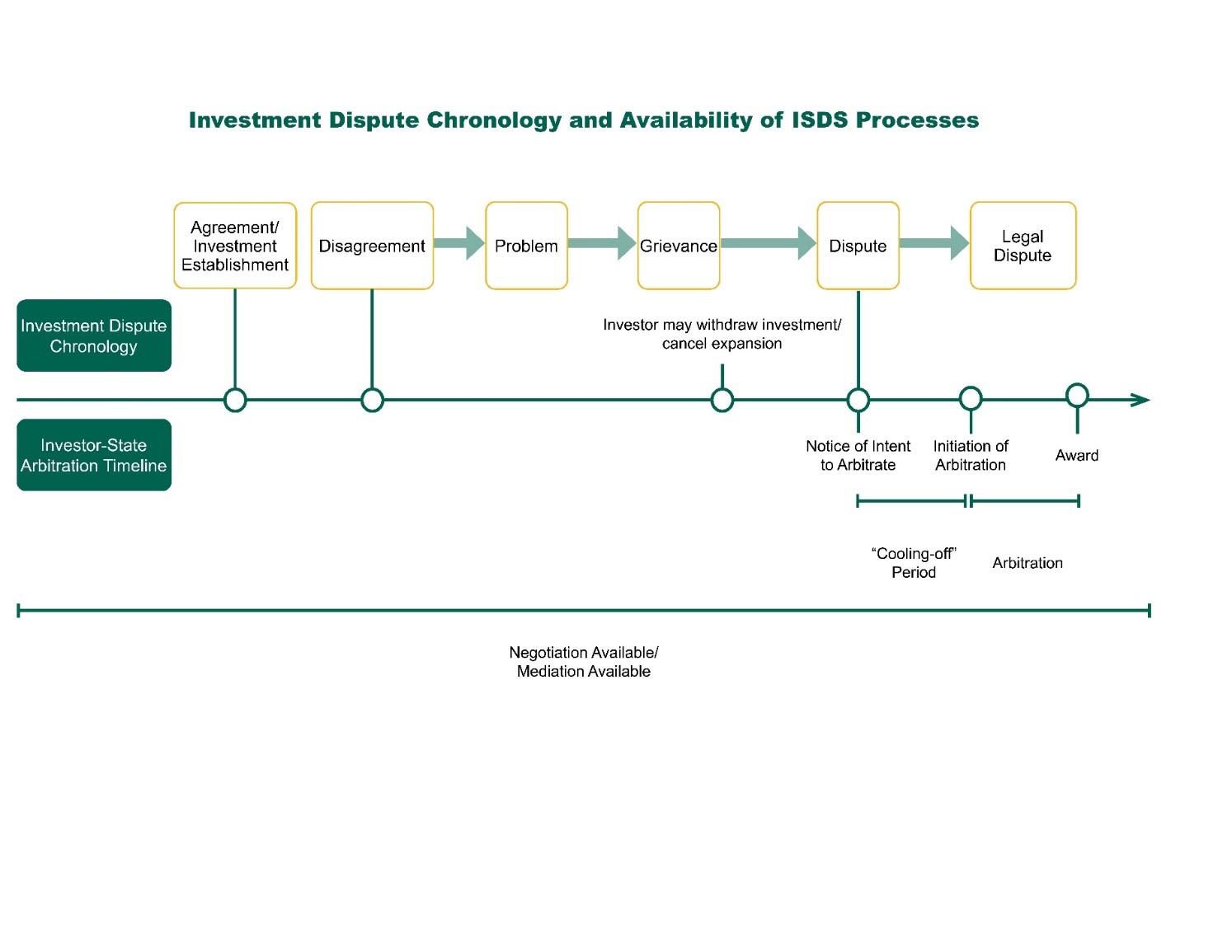

When is mediation best placed to offer an effective solution in the lifecycle of an investment or an investment dispute? As the assessment of which process is the most suitable one to resolve an investment dispute changes over time, it raises the question: when could mediation be a suitable process?

Mediation is in essence a facilitated dialogue between the disputing parties and therefore principally available whenever negotiation is an available option. Negotiation, and therefore mediation is not only an available process tool, as it is commonly understood, after a dispute has formally crystalized by a “Notice of Dispute” but could be used to resolve any grievances during the life of an investment. Mediation could also be used in conjunction with an investment arbitration to resolve all or parts of a dispute. This is the case even if the arbitration is far advanced, for example following a decision on jurisdiction or liability, or at any time when the parties consider it preferable to take control over the outcome.

Mediation can therefore be a suitable tool to resolve an investment dispute, or parts of an investment dispute, at various stages of the conflict, either as a stand-alone mechanism or combined with other dispute settlement options.

Mediation can therefore be a suitable tool to resolve an investment dispute, or parts of an investment dispute, at various stages of the conflict, either as a stand-alone mechanism or combined with other dispute settlement options.

Ultimately, weighing the factors noted above will help parties—and their counsel—to determine whether mediation is a suitable process choice to address an investment-related grievance.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.