I started mediating in my early 30s, surely old enough to know the difference between truth and fiction. Yet after a couple of years I began to say, first to myself then to my friends, that the concept of truth was ‘no longer useful’ in my work. What did I mean and how did I get there?

Journey from certainty

The first challenge to certainty came from conducting family mediation ‘intake‘ sessions: one to one conversations with both a screening and an information given/gathering function. I quickly realised people weren’t interested in what I had to say about mediation; but they liked a mediator who’d listen. First I would meet one parent. They’d often tell a tale of their difficult, unreliable and self-absorbed ex-partner. It would be utterly convincing, and I’d steel myself to meet this awkward individual. Then the second parent would turn out to be perfectly reasonable, even charming. Their story, a mirror image of the first, might select for emphasis the first person’s failure to recognise their children’s needs and self-centred unfairness.

A few months of this had an impact, particularly when combined with mediation practice. I became more sceptical of my ability read people and predict events. I learned that all is not what it seems. Sometimes the ‘baddy’ is the more wounded; and grief and loss can make perceptions extreme yet transient. My family and friends, having those conversations where you argue about who’s to blame for a divorce, found me a disappointment. I couldn’t join in. I was learning how little we know about other people’s inner worlds.

One client told me: ‘My wife’s problem is that I’m a born-again Christian and I never lie.’ I make no comment on his faith, but his approach to truth disturbed me and seemed to spell trouble for the forthcoming mediation (it didn’t go well.) Decades later I’m still piecing together why. It now strikes me that he was making a truth claim. He was, in effect, saying that he possessed a superior claim to determine the accuracy of his wife’s account. While she may tell stories, he spoke the truth. And he seemed to believe that these competing narratives would be determinative; that the outcome, and its ultimate justice or otherwise, would depend on who was believed.

Truth in practice

Readers may say that mediation doesn’t set out to be determinative ‘in that way.’ Helping people negotiate a practical and mutually acceptable resolution is not the same as establishing what is true and what is false. However, participants don’t necessarily share our pragmatism. Allegations of lying are common. I recently heard a highly skilled community mediator explain that her only ground rule is to prohibit the terms ‘liar’ and ‘lies.’ She’s learned how disastrous they are for our work.

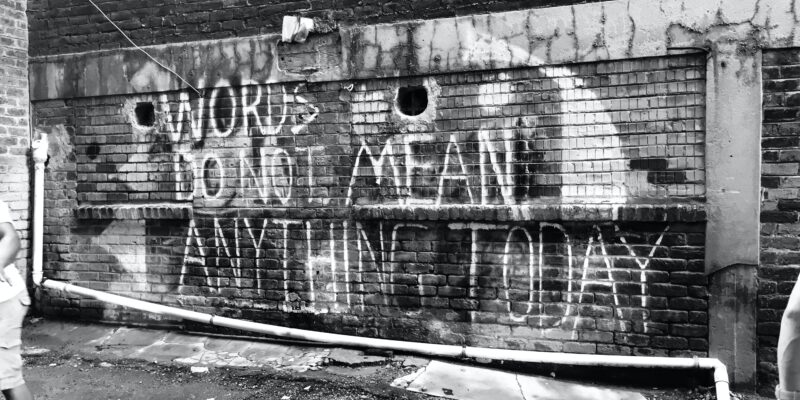

What are mediators trying to do here? It’s important to notice what I did not say. Recognising that the concept of truth was ‘no longer useful’ in my work is NOT the same as saying that truth no longer matters. I wasn’t even saying that truth doesn’t matter to mediators, nor that it cannot be known, nor that there is no such thing as truth and therefore no such thing as a lie. And the remark did not imply a commitment to relativism: you live your truth and I live mine.

With hindsight it seems that repeated exposure to competing truth claims drove me to ask the same questions as post-modern thinkers a generation or two earlier. Not ‘what is true?’ Rather ‘who gets to decide?’ Winslade and Monk’s concise summary of social constructionist thought in ‘Narrative Mediation’ asserts: ‘we might hear people’s stories of conflict as rhetoric’ (p. 40). What I was trying to say, rather ineptly, was that people’s attempts to convince me or the other party about their truth claims were unlikely to succeed. Worse than that, it would be oppressive to collude in a social encounter that enabled one person to close down the other’s perspective.

Mediation in practice

To be clear, truth does matter. But I’m not convinced that mediation is the best forum for its determination. Mediators are often accused of litigation-bashing; instead I’m calling for mediator humility. Courts and evidential hearings are set up to establish the veracity of competing truth claims. To be sure, they do this imperfectly (see Menkel-Meadow, 2006, ‘Peace and justice: Notes on the evolution and purposes of legal processes’ Georgetown Law Journal, vol 94, 553-580), but it remains a key foundation of the justice system. Judges’ decisions about ‘law’ rest on their assessment of ‘fact.’

However, mediators are not decision-makers (a state of affairs often overlooked by allies and critics). Parties make the decisions, even when legally advised. They already know their own perspective and the other person’s may or may not be influential. Montada and Maes argue: ‘The aim of discourse in mediations is not the search for universal ethical truths, but the furthering of the insight that good reasons can be put forward not only for one’s own normative views and claims, but equally for the opponent’s views and claims’ (‘Justice and Self-Interest’ in Sabbagh and Schmidt, 2016, The Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research, 109-125, 120).

They go on to suggest that rhetoric and persuasion be ‘banned.’ This is similar to my saying that the concept of truth is not useful in my work. Charlie Woods makes much the same point in his blog: ‘Your Truth, My Truth and The Truth.’ We are all acknowledging that a non-adjudicative process is likely to make little progress on that question.

Mediators learn to shift the terrain. More useful are questions like ‘what can you agree on?’ or ‘what needs to be dealt with here? or, my favourite, ‘what needs to happen?’ Mediators work on the premise that parties are best-placed to evaluate outcomes. The criteria by which they conduct that evaluation is a discussion for another time, though I touch on it here.

Truth in crisis

These thoughts have taken nearly 30 years to marinate. I might have left well alone but for an electrifying presentation last October at an online conference on ‘Presumptive ADR and Court Systems of the Future.’ The event marked the launch of presumptive (I’d say default) ADR in New York state. The most bracing ten minutes of an otherwise pretty positive day came from Prof James Coben, Senior Fellow at Mitchell Hamline Dispute Resolution Institute and one of my favourite mediation authors.

Speaking two weeks out from the US presidential election Prof Coben began: ‘Given the delicate state of our democracy… the threat to the rule of law and decline in civil discourse… I don’t think normal policy choices are called for.’ He explained that having lived through the four years of the Trump presidency he had become, in effect, a single-issue law teacher; actually not a ‘single issue’ but four issues. Before making curriculum decisions he interrogates them for their impact on: i) faith in public institutions and science, ii) surfacing and ending systemic racism, iii) the value, indeed necessity, of dissent and iv) helping citizens have conversations about acutely polarising issues dominating the body politic.

Space doesn’t permit a discussion of this fascinating talk, but his words on mediation in a ‘post-truth world’ caught my attention. I’m only an onlooker when it comes to US political discourse, but the overspill from its binary incivility washes across the world. Against that backdrop Prof Coben is not convinced that encouraging mediation meets his first criterion: restoring faith in public institutions and science. A self-confessed litigation romantic, he spoke of law’s unique ability to sort out fact from fiction. He asked: ‘Is it a social good to leave people to confront complexity by living their own truth?’

Conclusion – truth still matters, but it’s still not useful in my work

These words from a highly principled and thoughtful scholar ought to worry us all. Rather than an attack on mediation I prefer to see them as the expression of a profound crisis of confidence. The ground on which he stands seems so shaky that only a return to the certainties of the positive law feels safe. If scientific truth is under assault, the last thing we need is the acceptance of competing truth claims.

I’ll also resist more litigation bashing (another of Prof Coben’s targets). As I said above, mediators need to develop more humility in acknowledging what we can’t do. While law can’t offer scientific truth, it has developed the philosophical construct of evidential fact – actually, for civil disputes, the balance of probabilities. Nonetheless it is, mostly, effective. We mediators do not exist to replace the law, or the courts, or the legal determination of contested matters. We operate in another domain, one I’d argue can be equally principled.

What we do is help people talk or, if you prefer, negotiate (see John Sturrock’s recent blog describing Anna Howard’s research on this). In our adversarial legal systems, up until the moment the courts are asked to make a decision, parties are completely at liberty to negotiate anything (lawful) they choose. What I realised all those years ago was that, rather than replace the courts, mediators have to stick to their guns and insist that they do something else. They don’t determine truth and falsehood. They support conversation and negotiation. Sometimes that is all that’s needed for resolution. Sometimes those negotiators require external determination. That should not be prevented.

I’ll continue to insist that mediation is not the right place to resolve competing truth claims, but will be more cautious about how I say it. Truth does matter. Who gets to decide matters too. I still view it as a social good to extend to ordinary people the faith that they can make wise choices. My hope is that the winds buffeting the US legal system won’t rob us of our faith in human capacity for justice.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

Dear Sir,

I have been trying to come to terms with this issue myself. I decided to approach it from the point of view of defining “justice.”

I’m well aware that my first conflict resolution professor used to ask “whose truth?”

I however believe that starting from the point of natural law as against positive law we begin to have an understanding of where people’s truth comes from. It finds its origin in belief, philosophy and ideology. Quite often persons who put these beliefs first have a vested interest in a particular version of truth . Hence it helps to confirm that their belief system or ideology is correct.

Consequently for me, justice for a person of African descent cannot be found without a profound change in the views take of African history and culture. A similar thing would probably be said of a majority of Chinese or other asiatic cultures.

Truth then has to concede the need for knowledge and understanding of the “other.” Without such understanding we cannot find truth because we will always be operating in ignorance.

This discussion does not arise in every situation where we have to determine the truth but it often does and the fact that this happens often satisfies me that the approach suggested is useful across the board even in mediation where acknowledging one’s cultural differences may lead to an understanding of difference of opinion on many other topics.

Thanks for making these points, Francis. It’s the vested interest in particular versions of truth that troubled me, and still does.

Charlie, this is an excellent blog post making a very important point.

Thanks John. Appreciate it.

An interesting read. Prof Coben’s question resonates with me as a community mediator. I often wonder whether expecting people to sort out problems not of their own making or within their power to resolve (eg poor quality housing) through mediation is a social good. At least the process itself often produces social capital.

Thanks. I agree there may be other problems with mediation and Prof Coben eloquently highlighted some of them. Personally I’m not against revising our famous confidentiality obsession and reporting mediation outcomes, anonymously perhaps, so as to contribute to systemic change.

Very thoughtful post, Charlie. Thank you. It’s not a clearcut situation by any means. As an in-house lawyer I sometimes found myself in negotiations with opposing parties who would insist on a “truth” of a situation that was diametrically the opposite story I’d heard or had documented from our team. The most that I could say was that in my job I didn’t deal with truth as much as perceptions of truth, and I could only acknowledge that they were sincere in their belief.

But that was a counsel for a party, not as a mediator. Once, in a caucus with a mediator, my commercial colleague pointed out that $20 million of the other side’s demand was a duplicate calculation of a $10 million claim entered twice. It was an obvious and macroscopic error. My colleague walked the mediator through calculation error step by step. The mediator looked at him and said, in very neutral terms, yes, I can see how some people would see that is an error. As soon as the mediator left the room, my colleague turned to me and said, “he isn’t neutral if he won’t even accept the most basic math.” From that moment on, my colleague viewed the mediation process as a failed exercise that would not result in a settlement, and it didn’t.

Thanks Michael. That’s a salutary example. Mediators are held to quite a high standard. Do you think it would have been OK if the mediator had said ‘I see what you mean, but my opinion is neither here nor there. Can you explain that to the other side?’

interesting question. I think the answer is no. The “my opinion is neither here nor there” is what lost his neutrality in the eyes of my colleague, an engineer, whose language of communication includes mathematics. The mediator needed to speak at least the basics of this language, and acknowledge that $10 million plus $10 million = $20 million. He did not have to opine on the consequences of it.

The mediator could have acknowledged the evident math and asked my colleague to raise the issue with the other side and invite them to explain why they had included this in their damages spreadsheet.

Thanks again Michael. This is a fantastically useful ‘simulation’ with corporate counsel. I think I see my mistake. It would be wiser to omit the middle phrase. How about this? ‘Wow. I see what you mean. This looks very significant. I’m going to bring you together so you can explain it to the other side.’

My instinct to keep out of the way hasn’t diminished.

I love it. This would have done the trick! It would have gained his confidence instead of alienating him, and encouraged an exchange on an important point mediation.

Dear Charlie

Thank you for this thought-provoking and also very timely post. Maybe this concerns when truth is needed and when it is not – contexts.

Yes, we need efficient and trusted institutions – courts, elected bodies and lawmakers, and public admistration, and it is a great concern that trust in these is eroding, not only in the USA. I am seeing this here in Germany too, and it worries me.

We also need the scope to talk about perspectives and interpretations, as facts rarely stand alone. Mediation and facilitation are not about relativising truth or facts, but about understanding perspectives and what matters.

So I do not see a question of truth versus relativism. Restoring faith in institutions does not mean losing faith in mediation, but rather using it when it is appropriate and not using it when it is not, and being aware that that distinction is sometimes not easy to make.

As an example: the German Consitutional Court has today ruled that Berlin’s rent cap is not constitutional. This may reinforce confidence in institutions. The dispute is certainly one that should not have gone to mediation, it needed clarification by the courts. As a result millions of tenants are facing the possibility of back payments to their landlords. In some cases, this will involve hardships. Some landlords have already indicated that they may not demand full repayment. Could some of these cases be taken to mediation? If the parties are willing, yes. If that happens, will trust in institutions be harmed. I doubt it.

Best wishes, Greg

Thanks Greg. The German rent cap judgment is a good example of an adjudicative, precedent-setting decision, and confirms what I said about mediator humility. We’re not seeking to replace adjudication; it should be a partnership. I quite agree that mediating some of the implications of that decision for individuals will only contribute to a functional justice system.