I find myself writing this blog from South Africa, at the annual conference of the International Association of Conflict Management – http://www.iacm-conflict.org/. It is a fantastic melting pot of ideas, bringing together a range of cultures and identities. Cultures, at first sight, seem to describe national and group identities: South African, American, French, Dutch, Tanzanian, English, Scottish, Welsh etc. But there is another cultural mix going on: empirical researchers, social scientists, international conflict specialists, mediators and negotiators all have their own version of ‘the way we do things round here.’ We attend each other’s sessions and are enriched as a result.

But it’s hard to ignore the real-world backdrop to this conference. South Africa remains one of the most deeply divided countries on earth. Local people tell us that the gap between rich and poor has actually grown since the end of apartheid: little wonder, then, that the security industry is pervasive. Extensive European-style houses proclaim ‘armed response’ on the front gate, while a few kilometres away shanty towns look as if they were built on a rubbish dump. There is talk of calling in the army to deal with gang violence.

And yet this feels like a remarkably optimistic place. Again and again we hear people talking about ‘the transition’. Local mediators have fascinating stories to tell, of helping to negotiate strikes, or riots, or even funerals. In some respects they resemble mediators the world over: slightly maverick, personable outsiders who are also very comfortable dealing with business or employment disputes. And yet these stories speak of a preparedness to tackle the big stuff, of stepping up to the plate when the nation was in crisis.

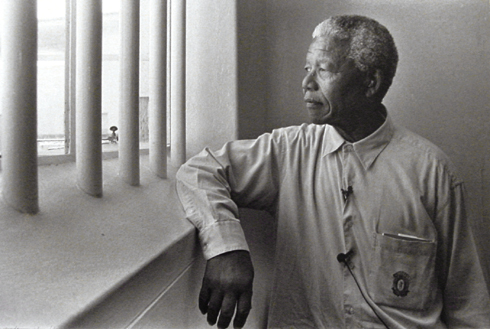

The most moving stories, unsurprisingly, are told on Robben Island (used by the apartheid regime to incarcerate black and other non-white political prisoners). It is a bleak place but we are grateful to step onto dry land after 45 minutes of yawling and rolling on the waves of two oceans. Our guide had spent five years in the prison. He describes for us the daily indignities, the seemingly trivial layers of inhumanity, like a daily allowance of 1oz fat for ‘coloureds’ and 1/2oz for ‘bantus’. He shows us the dormitories, the cells, the punishment block and the exercise yard (where Nelson Mandela was given non-prison clothes for a morning in 1966, for a Daily Express photo-shoot, only to have then removed again straight after). I ask him how he feels about telling us these stories. ‘At first it was very difficult’, he said, ‘but now it’s easier, like a kind of healing,’ and he puts his hand to his chest.

I sensed a strange familiarity about his manner, the way he spoke in such a matter-of-fact fashion about terrible things that most of us wish had never happened to anyone. He was quiet, unemotional and unflinching. As I walked back to the boat it came to me. He reminded me of some of my clients. When I first worked in family mediation I listened to tens or hundreds of stories like this, as victims of domestic violence (mostly, but not entirely, women) recounted the events that had led them to leave. Sometimes they cried, but mostly they were like this man, matter of fact and unemotional. The stories just had to be told.

Stories can’t be told to no-one. The listeners are crucial. We are welcomed to Robben Island by a little community of former prisoners, and even some guards (‘they were the good guys’ says our guide). I’m sure that the reason we are made so welcome on that island and in this country is this: if no-one hears the stories, no healing comes. These stories need to be told, and the world needs to listen. By extension, anyone who has experienced trauma needs to tell their story, in their own way, at a time of their choosing, to a listener they trust.

This is where mediators are uniquely privileged. We are invited into people’s lives at their lowest moments. Sometimes our clients choose to tell us very little. That’s their prerogative. But when they do choose to disclose something important we owe it to them, and to the wider world, to listen with all our might. In doing so, we honour their stories and allow the healing to come. In this way, the past does not have the last word.

That must be the hope for South Africa. This is a young country and many of the stories are optimistic. If nothing else this confirms to me that we are meaning-making creatures, and the people in this amazing place are working as hard as they can to escape the hold of the past. They need the rest of us to listen.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

Excellent post Charlie, thanks for sharing. Ana