While these mediations are commercial at heart, they beat with a cultural pulse and there is a sense of majesty as the Crown sits down to kōrero with Iwi … gather around, for the history of the real Middle Earth is not one of hobbits and magical rings, but of a people struggling to coexist in a far flung corner of the New World.

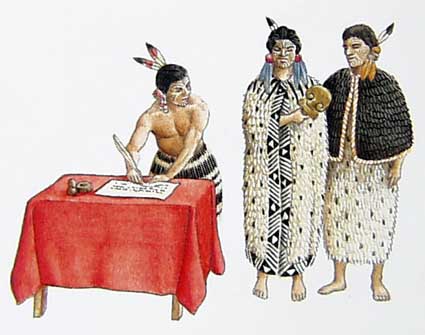

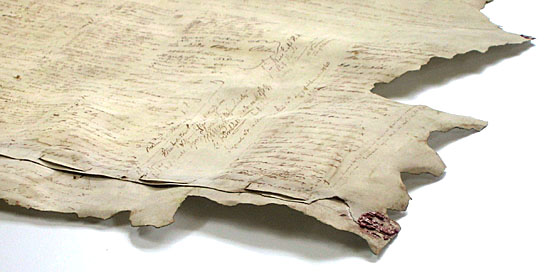

The Treaty of Waitangi was a written agreement made in 1840 between the British Crown and more than 500 New Zealand Māori chiefs. After that, New Zealand became a colony of Britain and Māori became British subjects.

Today the Treaty is considered to be New Zealand’s founding document.

It was drafted in English and then translated into Māori and it was presented to around 500 Māori at the idyllic seaside town of Waitangi on 5 February 1840. The next day, 6 February, more than 40 chiefs signed. Copies of the Treaty were taken around the country and many more chiefs signed.

Chiefs signed the Treaty because they wanted control on sales of Māori land to Europeans, and controls on European settlers. They also wanted to trade with Europeans and believed the new relationship with Britain would stop fighting between tribes.

Those who didn’t sign were concerned they would lose their independence and power and wanted to settle their own disputes. Some chiefs never had the opportunity to sign as the Treaty was not taken to all regions.

Even though not all chiefs signed, the British Government decided it placed all Māori under British authority. It did not take long for conflicts to arise between Māori and European settlers, who wanted more land. The government often ignored the protections the Treaty was supposed to give Māori.

In 1858 some Māori tribes selected chief Te Wherowhero to become the first Māori king, with the aim of protecting Māori land. The government thought this was a direct challenge to British authority, and invaded his lands. There were other wars between the government and Māori, and land was confiscated from several Māori tribes.

By the end of the 19th century most land was no longer in Māori ownership, and Māori had little political power. Pākehā settlement and government had expanded enormously.

Fast forward to the 1970s and 1980s and protests about Māori treaty rights became common as awareness of past wrongs grew.

This culminated in the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 that established the Waitangi Tribunal to consider claims that the government had breached the Treaty, and make recommendations to the government. Resolution of grievances under the Treaty remains an ongoing process to this day with the aim being to arrive at a Treaty settlement with all claimants, usually iwi or large hapu (tribes and sub-tribes) that have a longstanding historical and cultural association with a particular area.

A Treaty settlement is often a three legged stool;

1. A historical account, acknowledgements and a Crown apology

2. Cultural redress, for example – providing claimants with mechanisms to safeguard access to customary food-gathering sources or recognition of traditional place-names.

3. Financial and Commercial Redress (land and $)

Many Treaty settlements are hammered out directly between the Crown and claimant groups, some take decades to negotiate and some find their way to mediation during that time.

So it was that this week I came to be in a modern boardroom in Rotorua, an inland town located in Māori heartland and the ancestral home of the Te Arawa people.

The town is built precariously over one of the world’s most lively geothermal fields and sits squarely on the Pacific Rim of Fire. Māori have cooked and bathed in the natural hot water springs dotted about the town since the dawn of time. The dense sulphur deposits bubble and gush, as do the tourists who flock to see them, and give the town a pungent rotten egg smell that permeates clothing for days after visiting.

While these mediations are commercial at heart, they beat with a cultural pulse and there is a sense of majesty as the Crown sits down to kōrero (talk) with Iwi.

There are deep traditions at work here – age is to be respected, whakapapa (ancestry, familial relationships – unlike the Western concept of genealogy, whakapapa crosses ancestral boundaries between people and inhabitants in the natural world) is central and often, spirituality enters the room. We start with a hongi (greeting by pressing noses and forehead) which serves the same purpose as a handshake and we mihi (greet). When seated, we are led in prayer with a karakia by Kaumātua (elders) present.

Oral traditions are strong in Māori and the mediation takes on a formal air but gives way to dialogue as we proceed. Whakahīhī (arrogance) and whakamā (shame) of 150 years of breach go hand in hand. Modern day treaty partnership is a theme but past wrongs, handed down from generation to generation and often brutal, are never far from the surface.

The emotion of being able to reach out and touch redress is overwhelming for some. Tīpuna (ancestors) sit on the shoulders of others and they feel the weight.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.