“Racially discriminatory behavior may be reduced more effectively when racial issues are made salient rather than ignored or obscured.” (1)

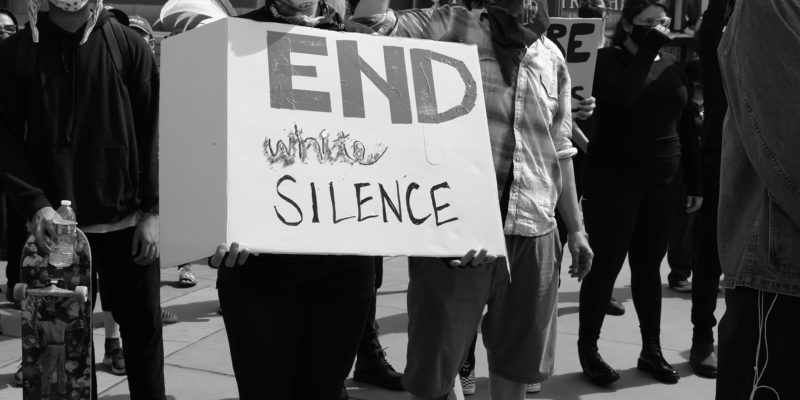

This week I’ve been thinking about white privilege. Ok, my white privilege. Like much of the planet I was horrified by the casual, almost routine asphyxiation of George Floyd. I wasn’t surprised by protest and fury; nothing triggers these quite like injustice. But in the last few days I’ve noticed placards insisting this is my problem as much as anyone else’s: ‘End White Silence’, or the more accusatory ‘Silence Is Violence.’ I’ve also noticed the protests spreading to my own city (Glasgow, Scotland) as we own up to the uncomfortable truth about our past. Our famous ‘Tobacco Lords’ were up to their necks in the slavery business. Exploitation is woven into our history.

So – what am I saying? What do I have the right to say?

The view from somewhere

There is no view from nowhere, so here’s a little of my perspective. I’m a white male in my 60s, married with children and an urban dweller. I grew up in a city that looked like a monoculture (with a small Asian community) but was in fact riven with sectarian prejudice and class division. The 1970s seemed a dangerous time to be a young man. However, my skin colour meant I wasn’t an automatic target. Other young men had to look for clues – in dress, accent, football allegiance – before deciding if I was friend or foe. And I had no particular reason to fear the police, though I now see this was as much to do with social class as race. A visiting US academic once expressed astonishment that in Glasgow: “you have white gangs?” Of course. Gangs sprout from poverty and disadvantage, not race.

I trained as a family mediator in the early 90s, when the field was dominated by women. Many had years of experience in dealing with people in difficulty and I was in awe of their presence and skill. But I can only recall one non-white mediator in Scotland. This changed little in ten years.

It was only when I took a Masters at a London university that I began to meet mediators from the UK black and minority ethnic community. But conferences and gatherings remained a largely white affair, particularly in the non-family world of commercial and court mediation. And even more strikingly so at the ‘high-value’ end. Again there are exceptions but they remain rare.

Yet the opposite is true of student mediation competitions. When I first took a team to the UK Student Mediation Competition in 2009 I was struck by the diversity. There were easily more women than men and some teams were all non-white. The same was true when we started going to the INADR tournaments in Chicago, and later when running joint summer schools in Glasgow with Chicago and Scottish students. I wrote about one memorable incident on this blog.

So what do my eyes tell me? First, mediation as a skill and a philosophy is highly appealing to young people from ethnic minorities. Second, those at the top end of our profession are much more male and white than those at the beginning (they’re not young either, but mediation takes a lifetime to learn and what’s wrong with some lines and grey hair?) These observations raise two questions in turn: Why is it so? And what are we (me included) going to do about it?

Why is it so?

I learned some answers to the ‘why’ question at a US legal mediation conference in 2017. (2) The theme was diversity, but it was difficult not to notice that there wasn’t a lot of it. One speaker (who belonged to at last two minority groups) made a simple point: mediation is, largely, a referral business. People tend refer to people like themselves. So it was tough for minorities to get a break, particularly at the high value end of the market.

Add to this the routine difficulty minority people face in obtaining employment. In Scotland in 2018 55.4% of the minority ethic population was in employment, compared to 75.1% of the white population. (3) We all know the importance of getting that first break. If you don’t get started you don’t gain experience. Without experience you don’t build skills and grow in confidence. And without skills and confidence you almost certainly won’t get into positions of leadership. Is it glass ceiling or sticky floor?

What are we going to do about it?

Here’s where I want to get specific. A good number of people who read this blog are in positions of authority, leadership or seniority. If we don’t initiate change we probably stand in its way. So what can we actually control? Well, one thing experienced mediators can often choose is their co-mediator (or ‘assistant’ if you must). Do we choose people who look like us?

Again I’m speaking to myself as much as anyone else. I think the time has come for the mediation profession to take seriously its stance on the issues raised by Black Lives Matter. I make a simple proposal: experienced mediators commit themselves to work with and mentor at least one person from a minority each year.

What would that look like?

It should include more than one mediation. In our mediation clinic at Strathclyde University I’ve noticed new mediators starting to get more comfortable/flexible at around the 20 cases mark. That’s quite a lot, but a busy practitioner could certainly aim to offer 5 or more.

It should involve de-briefing. I now borrow John Lande’s ‘Stone Soup’ idea for student assignments. Students are required to interview an experienced practitioner and write an anonymised case study of a recent case. The feedback is very positive. Practitioners and students clearly enjoy having the chance to talk in detail about the complexity of their decision-making. So I respectfully suggest that we make time to talk over what happened while it’s fresh in the mind. My own practice benefited hugely from sharing an office with an experienced mediator and just chewing the fat after tough cases.

We should monitor ourselves. The emotional arousal of these two weeks will fade but the issues won’t. Resolutions also fade unless we make a point of checking how we’re doing. Or better yet, hold each other accountable. I throw out the suggestion that professional bodies could include this commitment in their annual practice requirements. Let’s build positive incentives into our systems.

Do black lives matter to mediators?

I can’t speak for anyone but myself. I can’t control events in Minnesota but that does not let me off the hook in my own country. It has been difficult to write this post because of fear of being seen as a hypocrite. I haven’t done this before now. That has to change.

The key issue is not how we feel but what we do. And the key question, do black lives matter to mediators, must also be answered in facts on the ground: in a year, two years, a decade, how diverse is our profession?

Footnotes

1) Izumi C, ‘Implicit Bias and the Illusion of Mediator Neutrality’ (2010) 34 Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 71-155, p. 146. Available from https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol34/iss1/4/

2) 19th American Bar Association Section of Dispute Resolution Spring Conference, San Francisco, April 19-22, 2017

3) Black Lives Matter Scotland, slide presentation

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

Standing ovation. . . . . Thank you. 🙏🏾

A very important and powerful post Charlie, thank you. As you express so well, we can each enable, or inhibit, change.

Thank you for this. I hope it helps in creating opportunities to promising, young professionals from ethnic and other minority groups.