Given Peter Drucker’s memorable observation, how valuable an asset is trust in shaping a culture? What role could mediators play in strengthening it?

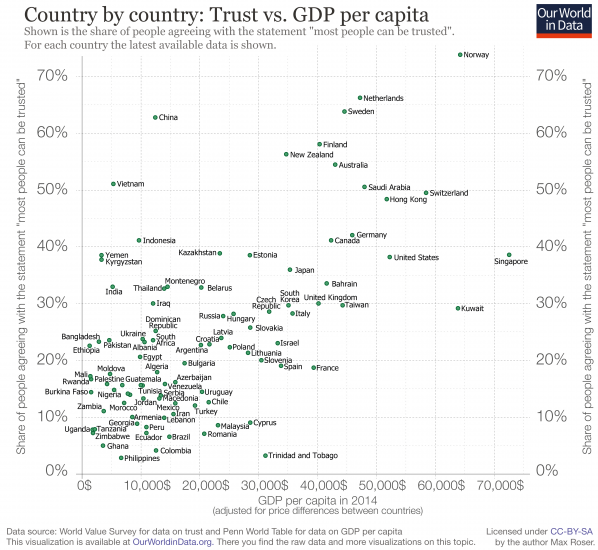

From a purely economic perspective there appears to be a strong relationship between levels of trust and output per head (as the chart below from ‘Our World in Data’ demonstrates).

As with any correlation questions can be asked about the direction of causality, but there certainly seems to be something going on. The relationship would appear to operate at both a macro and a micro level.

In the individual workplace cultures of trust have for some time been seen to promote significantly better performance – up to 50% higher productivity being reported in some cases. As an article in the Harvard Business Review, looking at the neuroscience of trust, summarised: “Employees in high-trust organizations are more productive, have more energy at work, collaborate better with their colleagues, and stay with their employers longer than people working at low-trust companies. They also suffer less chronic stress and are happier with their lives, and these factors fuel stronger performance.”

The article highlights the vital role played by leaders in building a high trust, high performance organisations. “Ultimately, you cultivate trust by setting a clear direction, giving people what they need to see it through, and getting out of their way.”

A key element of this sort of leadership is treating people fairly and with respect. In a recent book, ‘The Art of Fairness: The power of decency in a world turned mean’, David Bodanis looks at a number of case studies, such as Danny Boyle’s direction of the opening ceremony of the London Olympics and observes: “When fairness is applied with the right skill, it can accomplish wonderful things…better information; better creativity; more honest alliances.”One of the most important components of this type of leadership is listening carefully and being genuinely open to the ideas and perspectives of others at all levels of an organisation.

Trust also plays a vital role at a more macro level. In a short book published in 2014 Gert Tinggaard Svendsen of Aarhus University is in no doubt about the contribution that high levels of social trust play in the economic performance of Scandinavian countries, “Trust is Denmark’s invisible fuel”. In this regard it’s interesting that Francis Fukuyama’s widely adopted metaphor for aspiring state builders is “Getting to Denmark”.

High trust societies are more co-operative and have to spend much less time, money and effort checking up on each other, writing and monitoring complex contracts and policing free riding. To put it another way, their transaction costs are much lower and more effort can go into productive activity. A greater sense of security and mutual support also allows more scope for innovation, experimentation and learning as the costs of failure are less drastic.

A recent paper by Diane Coyle and others looks in more detail at the positive relationship between trust, social capital and productivity. In conclusion they note that the shock induced by the Covid pandemic is likely to impact on social capital. This is perhaps to be expected in a world of social distancing, with more working from home and growing online transactions. Quite how and in which direction this impact is likely to happen is something that policy makers and economic practitioners will have to keep a careful eye on.

It also looks like levels of trust can make a direct contribution to overall wellbeing of society. Perhaps not surprisingly, given what we’ve already seen, the World Happiness Report highlights the strong performance of Scandinavian countries over the years and notes the link to trust. “Nordic citizens experience a high sense of autonomy and freedom, as well as high levels of social trust towards each other, which play an important role in determining life satisfaction.”

The report also notes the relationship between inequality and trust when trying to understand the reasons for the high ranking of Nordic countries, making the link back to fairness. “One potential root cause for the Nordic model thus could be the fact that the Nordic countries didn’t have the deep class divides and economic inequality of most other countries at the beginning of the twentieth century. Research tends to show that inequality has a strong effect on generalized trust.”

In his recent memoir Barak Obama highlights the importance of trust in building and sustaining the post war social compact, which probably reached its most developed expression in the ‘Nordic model’. Obama characterises this compact as one that “at least tried to offer a fair shake to everyone and build a floor beneath which nobody could sink. He goes on, Maintaining this social compact, though, required trust. It required us to see ourselves bound together…each member worthy of concerns and able to make claims on the whole. It required us to believe that…nobody was gaming the system and that the misfortunes or stumbles or circumstances that caused others to suffer were ones which you at some point in your life might fall prey.”

Societies that do invest in building trust and strengthening relationships are likely to see significant returns over time in business and macro-economic performance along with stronger political institutions and improvements in overall societal wellbeing. A culture of trust between nations is also something that will be ever more important as we try to tackle the various, economic, social and environmental challenges we face that have an international dimension.

However, trust is not something that can be built overnight, it is a mutually reinforcing, circular and cumulative process that takes time. It can also be damaged and broken very quickly as a number of western democracies have discovered recently, as trust in each other and in many institutions has unravelled. Obama highlights the role that racial tension and economic crisis have played in undermining trust and providing opportunities for populist politicians to stoke feelings of anger, fear and resentment that can feed a negative downward spiral of mistrust.

Leaders of public, private and third sector organisations have a key role to play in nurturing a trusting and trustworthy culture, which is embedded in individual behaviour, social norms and institutions. Not least this will require them to lead by example, empower and enable others and treat people fairly and with respect.

Mediators and those with mediation skills can play a vital role in supporting leaders build a trusting culture by facilitating dialogue that allows people to feel they have been heard and are being treated fairly. In a recent article (interestingly titled ‘Why we should be more like Denmark’!) Paul Collier highlighted the importance of dialogue in developing adaptive communities in the context of tackling Covid:

“So how does a community become capable of acting together for some shared goal? The surest way is through dialogue and trusted leadership. Dialogue…engages everyone, so that all members of the community can participate and co-own the outcome. It flows back and forth between equals who aim to understand each other, in contrast to instructions flowing down a hierarchy. And it presumes mutual regard between participants, not indifference or worse. Dialogues tend to build a common understanding of a situation, a common sense of identity that can co-exist with our other identities. But above all, they can create a sense of common obligation that encourages us to put these collective purposes ahead of our own individual interests.”

The fundamentals of mediation are central to facilitating such a dialogue:

- separate people from the problem to allow a robust examination of issues in a respectful way

- ask the right questions, in the right way, to build understanding of different perspectives, thoughts and feelings

- help develop options and decision making criteria for moving forward in a way which adds value and takes account of different interests and needs

- support decisions on priorities to be taken as objectively as possible (for example, advising on cognitive traps).

There are various approaches being used, such as citizen’s assemblies, to promote more productive dialogue, particularly where difficult issues are faced. At the end of such processes there may still be the need for difficult decisions and trade-offs, which leaders or legislatures are required to make, but hopefully in this type of environment there will be less likelihood of misunderstandings and conspiracy theories which erode trust within society.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.

It’s an interesting discussion with well informed. I hope I’ll see more content like this in your future posts and Many thanks for sharing with us.

Nice information..