For a while now some of my mediations and facilitations have been taking place again in physical spaces, while others remain virtual, as does most of my teaching and training. The effects of Corona are still very much determining how people come together to work.

Having got used to the virtual world, I am now getting used to the world of offices and rooms with four walls again, and they are certainly not what they used to be. If there is one thing that I have found all of these digital and physical spaces to have in common, it is a new challenge in the skill of how to listen.

It may be that I am losing my hearing – I had another birthday recently and am getting ever closer to sixty. I think there is something in that. I will be looking into hearing aids soon.

We like to say that one of the very fundamental mediator skills is listening. I would say now: this has become a little harder. And: it still works just as it always did. Here’s why.

Listening is different in online spaces, and in the physical spaces I am returning to. I am reminded of the old sender-receiver model in communication theory, in which messages are liable to encounter distortion between sender and receiver, and much like the crackling old radios of my youth, this distortion is now so often technical and physical rather than in any way symbolic.

It is harder online because frequently enough there is a technical crackle, or someone whose microphone is too quiet, or too far from their mouths. Or because I cannot watch people’s lips as they talk, because there is a disjoint between sound and image due to the nature of the transmission, or in some cases there is no image at all. Or the connection fails for a moment, the sound is lost or incomprehensible. Or the people have chosen to sit with their heads side on to their cameras (possibly because they are using two screens and watching in the other), and it is harder to follow them when they speak. The effort of concentration when listening online is high, and participants in online meetings are not always modifying the way they talk to make it easier – by creating a clear camera presence, slowing down, speaking loudly and clearly, or staying brief, for example. And there is a limit to how far I would like to go to “instruct” them to be effective online speakers.

I have taken to listening actively to body language online, and to reflecting it back just as I might reflect back the words, ideas, or concerns I hear linguistically. “I see you shaking your head,” I might say, or “You are nodding,” or “You look sceptical.” This is something I used to do in physical rooms too, but much less. Listening online is, I would say, all in all a more comprehensive task than it used to be in the old pre-Corona offline settings.

Clients who prefer meetings in physical offices and meeting rooms – what has become known as “face-to-face” (though online is very much face-to-face too) – have been able to return to these formats. There are, however, restrictions. I facilitated a full-day workshop with a team of fourteen people, for example, which was held in a room that would easily have had space for fifty, and so that we could all remove our masks when we were seated the chairs were spread far and wide. Here too, it seemed that participants were not always able to project or modulate their voices, and it was simply hard to hear them at times. Now, I don’t want to too frequently ask people to speak up, even though I am sure that others in the room were finding listening equally hard at times. The technique of summarising becomes all the more important here. And everyone appreciated the chance to talk and listen to each other with the whole team present in an offline space for the first time in over a year.

There was a larger public meeting, with probably around sixty participants, with one central microphone that people were invited to walk up to speak (and which was duly disinfected after each person). To lower the barrier to participation, we also permitted people to talk from their seats, an opportunity many were happy to take. The space was an enormous converted barn, the voices seemed lost in the void, and I left my own stationary microphone and walked around to be closer and strained my ears, then repeated the gist of all the comments and questions for all those who had not heard, booming into the auditorium.

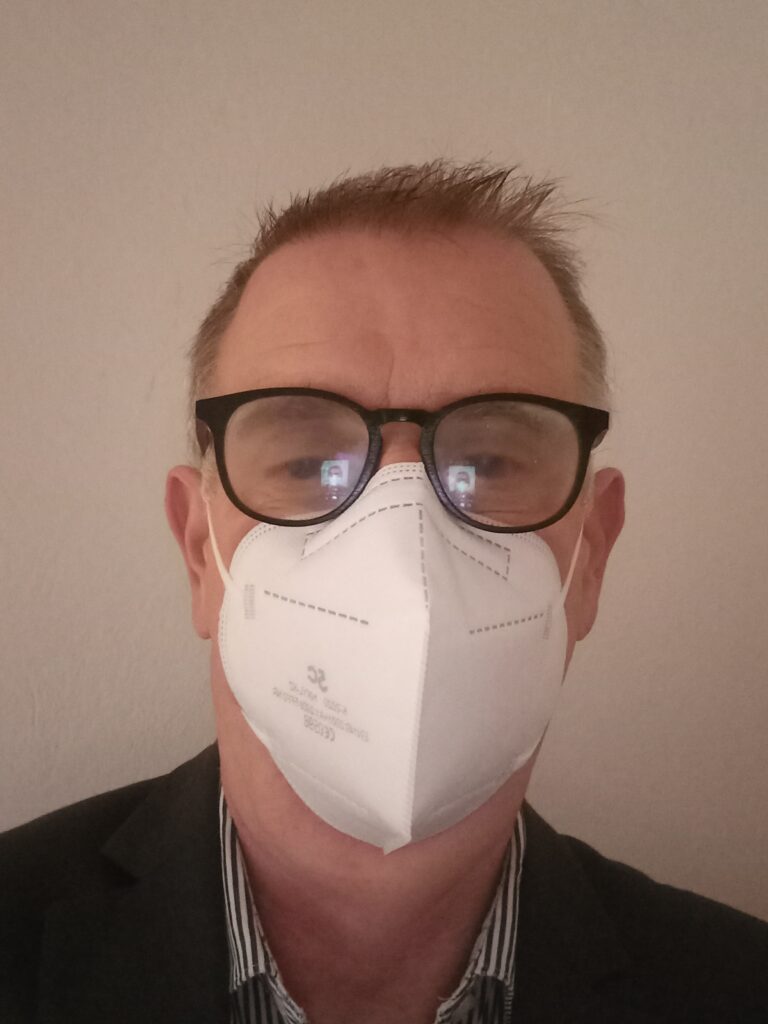

In a smaller setting, there were just three people in a room, though with some distance between us, and we were all wearing masks, while an air filter machine was humming all the time. The effort of listening when there is a mask in the way that numbs the volume, you cannot see the lower half of people’s faces, and there is a constant background hum was considerable. I also had to take off my steamed-up glasses every now and then and give them a wipe, so that not only could I hear less well, I was also having difficulty seeing properly. We needed “mask breaks” (with plenty of distance). But at the end the summary was that the conversation had been good to have.

One might say that it is better not to hold the mediation if these are the conditions under which it is held and to wait until things get back to “normal,” or that it would be better for the mediator to take better control of arranging the setting in advance. I do not think that the latter is always possible, and the former would be to be not offering the opportunity for a conversation. They say mediation is a flexible process. I think that Corona has changed so much that had been taken for granted about how people come together for meetings, and I have been experiencing a completely new sense of what that flexibility means.

Mediators pride themselves on their listening skills. I tell trainees that when summarising or reflecting back that it isn’t a matter of getting and repeating every single thing you have heard (though that is excellent practice in training too), but of being able to name the concerns and themes that matter, picking up on key words that resonate and offering them back so that the speaker can confirm that this is what matters (or not), and amplify if they wish. Thankfully, this still works.

Could it be that I don’t need to hear everything in order to listen to what matters? And could it be that clients who wish to work things out with each other will still do so under conditions that make listening harder – because they want to? And that it is the mediator’s (facilitator’s, moderator’s) job to keep on making listening easier. It is not the technology or the setting that makes things happen, but our states of mind.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.