Quite often, we hear mediators and mediation trainers using the fable of “Blind Men and an Elephant”, which is a story about several blind persons describing an elephant differently out of their own experience by way of their respective touches of the different parts of the same elephant, to illustrate that a party’s own interpretation of truth/reality is limited by that party’s knowledge, experience and perspective. ( see Charlie Woods’s post “Your Truth, My Truth And The Truth”, 3 October 2017).

Occasionally, the short story of “The Country of the Blind” by H.G. Wells is also cited. Nunez, the main character of the story, had the old proverb “In the Country of the Blind the One-eyed Man is King” on his mind when he first entered into this unique country of the blind. However, he very soon found himself being the inferior one. The country’s doctor was of the opinion that Nunez’s problem (i.e. with eyesight) could be cured and he could be perfectly sane with the removal of his eyes. Some mediators use this paradoxical story to make parties aware that one’s perspective, though seemingly to be an eternal truth, may be something else if the same is viewed in another context.

Most of us feel blessed to have the benefit of eye-sight. However, are we sure that we are able to see the truth or are we merely drawing our own conclusion by way of our interpretation?

On a personal level, I do have an ongoing experience on the relationship between vision and interpretation. My name is “Ting Kwok Iu”. Those who do not know me personally, upon reading my email, tend to reply and address me as Mr Lu or Mr Ting. They just could not believe their eyes that l have a surname with two vowels “i” and “u” together!

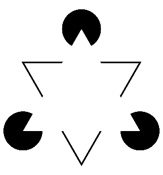

The Kanizsa Triangle is a more academic and effective illustration of the fact that our eye vision is governed by our interpretation of what we think we see rather than what we actually have seen.

There is no triangle but we all think we have seen one white triangle.

In recent years, psychology and neuroscience have played a more important role in the development of mediation. As a mediator and mediation trainer, I have started to think more about the relationship between human vision and the brain.

For most of the mediation assessments, a candidate is expected to use visual aids like a whiteboard or butcher paper in the joint sessions. Besides, a candidate is supposed to maintain balanced eye contact with the parties. These requirements seem to suggest that mediation is only for those who have vision and I of course am not comfortable with this.

Although I have not received any formal psychology training and I am not an ophthalmologist, I believe that those who do not have eye vision could still be excellent mediators. With such a belief and in order to assist another sector of our community to obtain mediation skills, I have decided to run a 40-hour mediation training course with three visually-impaired persons as my students on a pro bono basis in November 2018. The proposed course is not only to benefit my three students but also myself as I hold the view (which is yet to be proved) that those without ordinary vision must be able to see something that we tend to ignore given the fact that they possess powerful listening skills.

“Science is for everyone,” Wanda Diaz Merced, a blind astronomer, says. “It has to be available to everyone, because we are all natural explorers.”

“Mediation is for everyone,” I say. “It has to be available to everyone, because we are all natural peacemakers.”

If any of the readers of this blog have the experience of running a mediation training course for the visually impaired, please share your experiences with me.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Mediation Blog, please subscribe here.